The protests in Wisconsin may be a big turning point for organized labor in America. It's not yet clear whether Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker's plan to end state workers' collective bargaining power will destroy the unions in his state or whether it will actually re-energize them — both in Wisconsin and nationally.

What is clear is that we're all spectators in a pretty significant chapter of history: the history of organized labor in America.

And recently, we went to a place that can probably be described as a kind of Bastille or Lexington and Concord of that history.

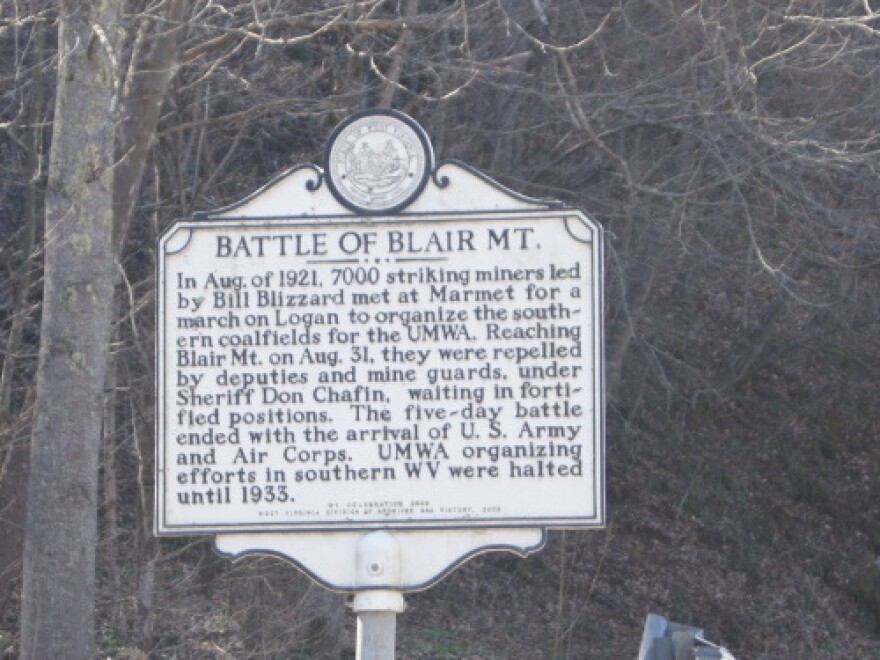

It's called Blair Mountain, and it's located in a southern pocket of West Virginia.

In late summer 1921, Blair Mountain was the site of the largest uprising in American history since the Civil War. It was the only time in history that U.S. air power has been used against American civilians.

"This is what's left of the town of Blair," Kenny King tells Weekends on All Things Considered host Guy Raz, as they stand next to a stream. "There, maybe, I think I counted maybe about 35 houses left."

King is a third-generation coal man. His grandfather and father were miners. King himself works as a chemical analyst for a coal company.

And here in Blair, in Logan County, W.Va., well, is the heart of coal country.

"It's been underground mined a lot, but there's still quite a bit of coal left," King says. "Yeah, there's millions of tons, I'd say, in that area."

A Coal-Fired Country

West Virginia's been called the Saudi Arabia of coal. It produces more than a third of all the coal mined in the U.S. More than half the energy Americans use is powered by burning those black rocks. The lights in your house, your TV, maybe the computer you're reading this story on — they all work thanks to coal.

The other thing about West Virginia is its poverty rate, one of the highest in America, even though coal prices just hit a 15-year high.

Almost a quarter of the people in Logan County live below the poverty level. They're people left behind by the changes in technology and technique that have allowed coal companies to earn more money and hire fewer miners.

This story, though, is only partially about jobs. It's really about history — the battle over what to remember and whether to remember it at all.

A Firefight To Organize

No one has the exact details of what happened here in late August/early September 1921, but the basic story says around 10,000 coal miners took up arms against the private militias employed by West Virginia's Stone Mountain Mining Co. For five days they fought for the right to organize — to join unions.

"From all the artifacts found here, there had to be hundreds of men up here," King says. "I mean, there's probably thousands of shell cases scattered around here."

As many as 100 men died in the fighting. It got so bad that President Harding sent a detachment of federal troops to crush the rebellion.

None of this happened in a vacuum. Tension had been building for years. Just a year before, union-busting mercenaries, who worked for a private agency called Baldwin-Felts, shot and killed the pro-union mayor of the nearby town of Matewan.

At the time, most states had laws against organizing. It didn't help that Harding's administration was decidedly anti-labor.

The worry was the unions would bog down industry and put the brakes on America's rapid economic growth.

The problem for the wage earners, at least in Logan County, was that they didn't have a whole lot of options.

A Company Town

"They had the yellow-dog contract which said that, basically, if you took a job at this mine, you could not associate with anyone in the union, you couldn't join," says Doug Estepp, a local historian who runs tours of the area. "You were basically fired, blacklisted and evicted — and probably beaten on the way out by the guards just for good measure."

The coal companies owned your house, they paid you in credits that could only be spent on highly inflated food at the company-owned store, and if you complained about safety, you were fired.

The private security men from Baldwin-Felts would threaten, beat and sometimes murder agitators — all with impunity.

And so it all came to a head in late August 1921. The miners of Logan and Mingo counties had had enough.

Back in the '70s, a documentary called Even the Heavens Weep featured a few of the survivors of the battle, including Paul Maynard.

"I don't know, there was thousands around here, but they was coming in from Illinois, Pennsylvania and Ohio, the miners was," Maynard said. "They told the government that if they didn't open up Logan County, that they was gonna open it up themselves and blow it away."

Although the workers outnumbered the coal company guards, they were also outgunned.

"They were facing big odds. The coal operators had machine guns, they had tommy guns, a lot of high-powered rifles. They even had a small artillery piece up on one of the mountains here — we're not sure where," Estepp says.

After five days, the rebellion was crushed. Hundreds of workers were tried for insurrection and treason. The legal fees bankrupted the United Mine Workers Union, and for the next decade, it almost disappeared.

A Historic Site? Some Object

Every few weeks, King comes up here with his metal detector to find spent bullet casings. More than a million rounds were fired in those five days. And every time he's up here, King finds them.

Two years ago, Blair Mountain was entered into the National Register of Historic Places. And then, just a few months later, it was taken off by state officials.

Lawyers hired by West Virginia's largest coal companies came up with a list of landowners who, they said, objected to the designation.

"There's apparently a lot of money to be made by blowing this mountain up and taking all the coal out from it," labor historian Gordon Simmons says, referring to mountaintop removal.

A lot of the land around Blair Mountain is owned by coal companies, including the biggest ones, Massey and Arch. For now, the state hasn't given permission to mine this immediate area. But, judging by the number of tractors and heavy machines already deployed here, preservationists like King think it's just a matter of time.

"They already approved that area over there," King gestures. If it's not designated as a national historic site, he says, the spot where we're standing will be turned into a flat, grassy field.

King believes this is hallowed ground, like Gettysburg or the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., places where America's history was forever changed. But he's had a hard time making that case to the folks in Logan County — a place where every fourth person is out of work.

'That's All I'll Ever Know'

At the Go-Mart gas station, about four miles from the mountain, mine workers stop by to grab pizza and hot dogs before heading off to the night shift.

There are only about 16,000 miners in West Virginia today. Mountaintop removal doesn't require as much manpower as underground mining. These are coveted jobs; they pay well. So for the most part, miners are more interested in seeing the economy grow than preserving what they see as just another mountain.

One 22-year-old named Jordon sums up the consensus view around here: "We got to mine the coal to make the money. Period. That's all there is to it," he says. "I've been around this my entire life. My dad was a strip miner, my grandfather was — that's all I've known, that's all I'll ever know."

About a 90-minute drive from Logan County, at the ornate state Capitol in Charleston, Simmons is part of a group trying to get Blair Mountain back onto the National Register. He says the struggle isn't only about jobs and mining rights. It's also about whether to remember Blair Mountain or to sweep it under the rug.

Just as in 1921, Simmons says, when West Virginia's political establishment was wholly controlled by coal interests, "things haven't changed that dramatically, that the long arm of King Coal can't reach into state government and make things happen in its favor."

Just this week, West Virginia's historic preservation office started the process to get Blair Mountain back on the National Register. Landowners have until April 1 to file objections. Unless more than half of them do object, the application heads back to the federal government for consideration.

"This is a political fight, this is a social fight, this is a fight about our history, our heritage, our culture," Simmons says. "It's a fight about what kind of society West Virginia is going to be going forward and what has been in its past."

The irony about Blair Mountain is that it nearly destroyed the union. It would take 15 years until the National Labor Relations Act would revive it.

But Blair Mountain was a pivotal moment, and if it does finally get a spot on the Historic Register, there's a good chance the story of what happened there will also find a more prominent spot in America's collective memory.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))