Behind every great pop music genre, there's a record label that launched its stars. Blue Note pushed Theolonious Monk and Art Blakey into the mainstream. Sun Records brought us Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis. Motown had its glittering roster of the Supremes, Stevie Wonder and more.

For hip-hop music in the early 1980s, that label was Def Jam. A new book attempts to capture that history in photos, interviews and essays. It's called Def Jam Recordings: The First 25 Years of the Last Great Record Label.

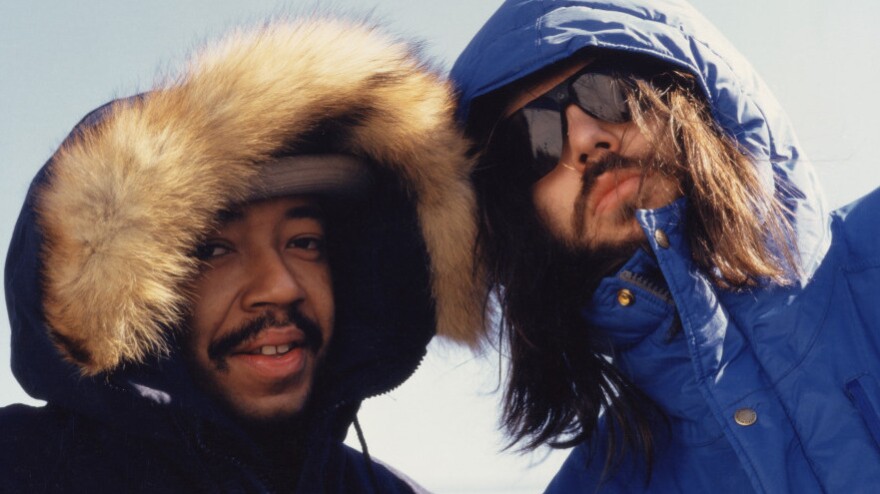

LL Cool J was just 17 when he became one of the first artists signed to the company. The men who founded the Def Jam label in 1984 weren't much older. There was Rick Rubin, a 21-year-old NYU art school student from Long Island making music in his dorm room; and Russell Simmons, a 27-year-old from Queens, who was already making a name for himself in the downtown scene with his brother's rap group Run DMC.

Weekend Edition Sunday host Audie Cornish spoke with both founders separately about the early days of the label.

Interview Highlights

On The Partnership Between Simmons and Rubin

Simmons: I met him and he had a drum machine full of hot joints. I mean his whole DMX machine was full of hit records, from what I could hear. He was a smart kid. And he was part of a band called the Beastie Boys, who I met later. They were phenomenal, and he was a great producer. He had produced that record "It's Yours" by T La Rock and after he produced that record he started receiving tapes, and one of the tapes was LL Cool J's "I Need A Beat." He remixed it, or redid it, and it became our first release for Def Jam records.

The more I got to know Rick, the more I felt that my efforts should go into the partnership and not into a separate company. Because I already had Run DMC and Whodini and Jimmy Spice and Kurtis Blow and the Fearless Four. I was managing a lot of acts and I was ready then — and I had produced a few acts that were successful, including Run DMC. But then I saw Rick wanted to start a record company as an independent company, as opposed to some distribution deal, and it made sense. I put the money in with him — it was only a few dollars — and the first record, "I Need A Beat" sold so well. And it was not the sales of the records; it was the sound of the records that inspired me to be his partner. He's a great producer and I thought, "We can do a lot together."

Rubin: Russell and I met at a party for a TV show called "Graffiti Rock." It was a pilot episode and Run DMC appeared on it and the Treacherous 3 appeared on it and it was in a loft somewhere on the West Side in the teens. But I remember being really excited when I met him because, as a fan of hip-hop, he had already — you know his name on a lot of the rap records that already came out — Kurtis Blow, Run DMC — so I was excited to meet him. And when I met Russell he, it turns out that "It's Yours" was his favorite record, which was a surprise to me. And he was really surprised when he met me because it was, because he didn't picture me as I was, based on what the record sounded like.

[Russell] was five years older than me, and he was already established in the music business. And I had no experience whatsoever. So even then he was the face of hip hop, even before Def Jam he was the face of hip hop. It's true! If you had a club and you wanted to hire a hip hop artist, you called Russell and he would get you a hip hop artist. Or if you were a record company and there was a hip hop artist you were interested in signing, you'd call Russell, because he was the center of hip hop from before me, before we ever met.

On Aiming For The Mainstream

Simmons: The radio was listening to, or playing records like Patrick Juvet's "I Love America" or "YMCA" by the Village People, and that's what black radio in New York sounded like. It was disco. And there was a rebellion in the streets, and kids played funky records, whether it was a jazz, or a blues, or a rock and roll, or a funky R&B band like James Brown, they would play those backing tracks and they would rap over them and create their own music, something that was a better soundtrack for what they were living. And that was the creation of hip hop as an expression for people who felt locked out of the mainstream."

I also had a complete disdain for what was the mainstream. It was like as a kid I was just rebelling. I didn't want to hear anything, any instrumentation that sounded like it was already on the radio. I wanted to do something new. And all the records I produced, we made sure that none of the instrumentation that sounded commercial, or were part of the mainstream, were in it. It was kind of like, the producers would come, and musicians would come and we'd just ask them, "let's create new sounds" or "let's not use anything but drums.

Rick and I had that together, yeah. I did that and I met Rick and he felt the same way. In fact he was even — not so much as a rebellion from the R&B things that really offended him, as a kid offended me or made me feel locked out, I felt different from the traditional black record execs — but Rick was from a different background anyway. So when he heard "Rock Box," or he heard some of the records we created, they inspired him because they were closer to his sensitivity.

Rubin: I was a fan of rap music since I was in high school, and there was a radio show called "Mr. Magic's Rap Attack on WHBI", and I would listen to that every week and it was on for an hour — and during that hour that was the only place you could hear hip hop on the radio - and I'd listen to it and would record it every week on a cassette recorder — and then listen back to it all week. I liked punk rock, and it seemed like a new breed of punk rock to me.

Well I listened to mostly rock music, and I felt like hip hop was like an extension of rock music when it was done well. So energetically, again I felt like it was in line with punk rock and maybe hard rock, more than it was in line with R&B, which I never really liked. I liked certain artists; I liked James Brown, for example, but wouldn't say I listened to the R&B that was on the radio either."

So up until the time of Def Jam, pretty much most of the rap records at the time were R&B records with people rapping on them. And then I think one of the things that separated our records from the ones that came prior was that they had more to do with what the actual hip hop culture was like, and that was only because we came as fans from this culture and, in making the records and producing the records, the goal was to capture the energy that you felt at a hip hop club — and they weren't really clubs then, they were more like a hip hop "night" at another club. So if you went out and you saw DJs and MCs and the energy that would happen on that one night, that's was really what we tried to get into the records.

On The Beastie Boys

Simmons: They came and they wanted to be rappers, so they wore red shiny sweatsuits — red Pumas and red sweatsuits — and I thought it was better when I saw them in their punk band — they had a punk band — and the way they dressed, in those outfits.

Since they had such an original sound and original ideas, they should dress from their heart. And I think they did eventually and — I think it's important that they did, and in every case, for all the artists, that kept it real. There was a costume in the street for Run DMC — the costume was a leather suit and a velour hat — but you could wear that to a party and nobody would point you out except to say you look good. But it wouldn't be — it was a uniform for the street, more than it was a costume, you know?"

Rubin: Yeah. We definitely had track suits. It was fun and funny and it was really because we liked the whole culture and wanted to be part of it."

Russell was, I think, instrumental in getting them to look more like themselves. And musically we just tried to make our favorite hip hop album, and I was probably very vocal about the idea of it being a true hip hop album and not being an album that the band played on but more of a classic hip hop album. But a ridiculous hip hop album, you know. Talking about things most hip hop artists wouldn't talk about, because, again, we were coming from outside of this community, watching the community, and being excited by the community, and um, so there was more of a fantasy element. But there, honestly, in a lot of hip hop, like if you listen to Kurtis Blow records a lot of it he's talking about fantasy situations, or if you listen to Africa Bambataa, you know he's talking about what feels like space-age ideas, and it didn't relate at all to their lives in real life. So a lot of what the Beastie Boys talked about were things we thought were funny and entertaining and in the zeitgeist at the time.

On Authenticity

Simmons: Yeah, it was a big deal. It made it just feel — authenticity sold Def Jam, and honesty. And I think that's what made rap such a stable footprint in culture, that it's so honest. I mean people are sexist and racist and homophobic and violent. But I don't think of the rappers as being any more sexist or racist or homophobic than their parents. Certainly less, in all those cases, less homophobic or racist or sexist, and then less gangster than our government. It's stuff that people normally don't speak on, subjects they don't speak on, and ideas they kind of keep to themselves."

We did the opposite — we took whatever charm they had that was produced and created and we let them do what was more honest and obvious. "Artist Development" meant looking inside, as opposed to trying to make them fit in. So it was the opposite strategy in some ways, because we would look to produce their inner ideas, as opposed to what the world was looking for. And the more we went inside — the expression came, "keeping it real," that was always the artist development strategy for Def Jam. 'Keep it real.'"

Rubin: I can remember when we made the video for "Going Back to Cali" — LL Cool J video — and I had a strong feeling of how LL should look in the video. This was at a time when rappers all wore a lot of gold jewelry. And I was very insistent that LL not wear any jewelry. And it was a really contentious issue. And I remember him calling Russell and saying, "Russell! Rick doesn't want me to wear jewelry in the video!" and "I can't do this!" and Russell, to his credit, said "No, listen to Rick, do what he says." And it ended up being a really special video, and I tried to explain to him at the time, like "the reason you don't want to wear jewelry is because everyone's wearing jewelry. And it's much more interesting when everybody's wearing jewelry for you not to." And he was like, "How are people going to know I'm successful if I'm not wearing jewelry?" And I said, "Because you're so successful, you don't need jewelry!" Eventually he made the video and since then we talked about it — he's happy he's not wearing jewelry in it. So it all has a happy ending.

On The Music Business

Simmons: Well I don't think we had any good experiences. They just didn't really get what we did. I can tell you a funny story [about] when we tried to sell "I Need a Beat." We were sitting with a lot of senior executives at Warner — the chairman of the company brought me in, Mo Austin, and he played "I Need a Beat." And "I Need a Beat" was an emotional record. And they bowed their heads and listened intently — it was a weird scene for us because imagine all these guys in these suits and ties and they're bending their heads down and listening to "I Need a Beat" by LL Cool J? They're not bobbing their heads either, they're just listening, like it was a beautiful ballad!

And I got up and I knew I didn't belong in that room, and we left and no one ever called us again. Eventually I went back to Mo Austin and he funded — helped to fund — the movie "Krush Groove," and took the soundtrack. Warner Brothers made the movie, and it was No. 1 in the country.

Rubin: I don't remember at all what people said at the time. I remember we were surprised that people liked it, or that it got as successful as it did because in making it we were really trying to make something just for ourselves, you know something we would love. At that time there weren't really a lot of big rap albums, so the idea of anybody else liking just seemed — it didn't seem realistic. It was a real surprise that it ended up sort of breaking out and affecting people all over the place. Strange.

My parents always wanted me to go to law school, but at the same time were supportive of the things that I liked. I looked at it as a hobby, I never looked at it as a job, and then the hobby sort of took on a life of its own and ended up becoming a job, but I never knew that it could be, I didn't even know that it was possible to be.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))