A Nevada water agency has taken the first concrete step toward accounting for evaporation and other losses in the Colorado River’s Lower Basin. The new analysis attempts to pinpoint exactly how much water is lost, and who should cut back to bring the system closer to a balance between supply and demand.

An analysis compiled by the Southern Nevada Water Authority estimates the total amount of water lost in the river’s lower reaches. If implemented in its current form, the proposal would translate to significant cutbacks for users in Nevada, Arizona and California.

The agency’s staff presented the analysis to representatives from the seven U.S. states that rely on the beleaguered Colorado River for drinking and irrigation water supply. Federal officials were also present at the Manhattan Beach, California meeting held in the third week of October.

Farmers and cities in the river’s Lower Basin states of California, Arizona, and Nevada have never had to fully account for the amount of water lost to evaporation, or to leaky infrastructure, also called transit losses.

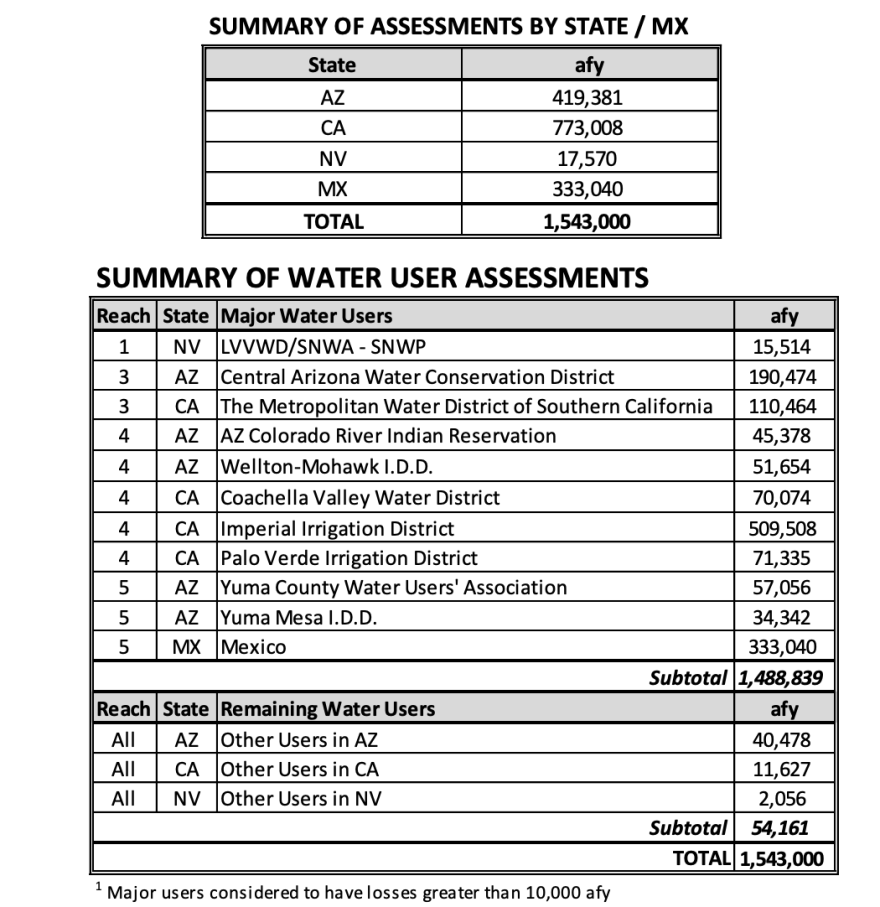

About 1.5 million acre-feet of water is lost to evaporation and other losses each year, according to the Southern Nevada Water Authority analysis. That’s more water than the state of Utah uses from the river annually. One acre-foot is the volume of water needed to fill an acre of land to a height of one foot, or approximately 325,000 gallons.

“This is work we had started internally a little while ago to get our heads around, what is the exposure to our community? And how do we make sure we have an adequate water supply?” said Colby Pellegrino, the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s deputy general manager.

The analysis examines where water loss occurs downstream of Lee’s Ferry in northern Arizona to the northern boundary of the U.S.-Mexico border. Both the U.S. and Mexico rely on the river. The analysis divides the river into five reaches, and includes the large reservoirs in the Lower Basin -- Lake Mead, Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu.

The analysis then calculates which states and which users within each state could be cut back to account for the overall basin-wide loss. Users upstream, like the Southern Nevada Water Authority, carry a lesser burden than those downstream, as users upstream are not reliant on downstream infrastructure and reservoirs to deliver their water supplies. Those users further downstream on the river, like California’s Imperial Irrigation District, would face the highest volume of potential cutbacks, factoring in their placement on the river and their volume of overall use, according to this analysis.

There is no set standard to account for these losses, Pellegrino said, and this initial analysis is meant to get the conversation started as a potential model for how to divvy up the cuts among users.

“We can't even build consensus unless we get a straw man out there and start talking about what the different elements of such a calculation might be,” Pellegrino said.

Using the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s methods, the river’s big users could be staring down significant cuts to their supplies to account for evaporative and transit loss. To achieve the total savings of 1.5 million acre-feet per year, the analysis assigns cutbacks of 509,508 acre-feet on the Imperial Irrigation District, 190,474 acre-feet on the Central Arizona Project system, and 110,464 acre-feet to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, with the rest being contributed by dozens of other smaller users.

Mexico, which is able to store some of its river water in American reservoirs because of binational agreements, is by treaty not required to share in transit losses. But if the country were to share in additional reductions related to evaporation and transit loss, the country’s total could be 333,040 acre-feet per year when considering its total uses and its placement as the river’s final user, according to the analysis.

Accounting for evaporation has become a rallying cry from users in the river’s Upper Basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico and a tension point in ongoing negotiations. Those states already use a system to track losses and are charged for them in their basin-wide accounting. Upper Basin water managers say the current system is unfair.

“This is something the federal government must do right now,” said Andy Mueller, director of the Colorado River District, a water agency on Colorado’s western slope, at a September public event. “They have the right to do it under the [Colorado River] Compact. They have the right to do it lawfully. They just don’t want to do it because it hurts and it’s maybe going to bring in litigation.”

Federal officials have identified the issue as a short-term priority. At a September gathering of water managers in Santa Fe, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland told attendees it was time for a “candid conversation” about evaporation and transit loss.

In June, Bureau of Reclamation commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton told members of a Senate committee that the river system required an additional two to four million acre-foot reduction in use in order to stabilize its largest reservoirs. Accounting for evaporation could be one step toward achieving that overall reduction, water experts have said.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation.