The messages covering Haystack Rock's graffiti-stained surface are not for the faint of heart. Take the mustard-yellow words spray-painted on its southwest side:

"F.U. CSU."

Move a few steps to the left and you'll get an entirely different picture: A carefully planned mural for a lost loved one.

For generations, people have flocked to the behemoth, 40-ton rock north of Fort Collins to talk trash, make blunt political statements or commemorate the lives of people who have passed away — all through artistic expression. But who are the people behind these paintings?

KUNC listener Laura Ornowski-Hildebrand recently asked us that question through Curious Colorado.

"I've only been a Coloradan for a decade and I really am fascinated by the history," Ornowski-Hildebrand said.

The beginning

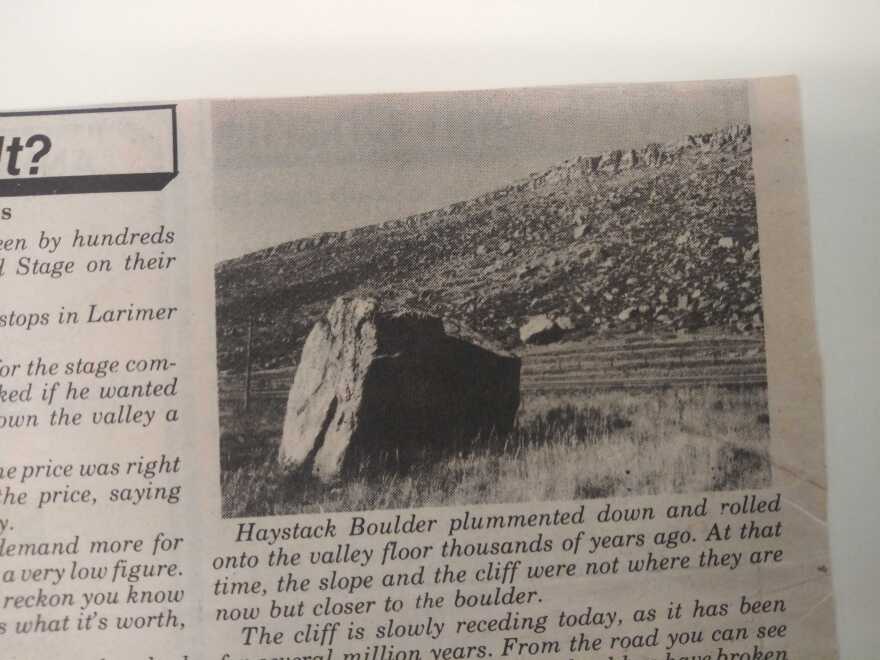

The granite boulder likely broke off from nearby sandstone cliffs millions of years ago. It then tumbled down the hillside onto a grassy clearing where it sits today, less than 100 feet off of Highway 287.

The land where it sits has changed hands over the years. Its current owner, the Northern Water Conservancy District, purchased it in the mid-1980s. Now staff include it as a stop on tours.

Brian Werner, Northern Water's communications director, keeps a fact sheet on hand for curious visitors.

"In some ways it's become a First Amendment billboard through the years," Werner said.

The name "Haystack Rock" comes from a local legend.

Back in the frontier days, a farmer decided — for fun — to cover the rock with hay. The idea was to make it look like a larger pile than it really was, Werner said.

A highland rancher, who was new to town, then showed up to ask if it was for sale.

"Sure," the farmer said. So, the two agreed on a price.

The rancher went back to town and bragged about his "amazing" deal to friends and family. The next day, he brought his wagon back.

But by that time, the farmer was long gone.

"When he stuck his pitchfork into the hay, it scraped against something hard, like a rock," read a 1973 Triangle Review article about the con.

"The guy had been duped," Werner said. "And it became Haystack Rock."

Depending on who's telling the story, sometimes it's the Union Pacific Railroad or the military being scammed, Werner said.

"This sort of thing builds up legends throughout time," he said. "All we know is it had to do with somebody stacking hay around it."

As far as when the tradition of painting the rock started, Werner guessed sometime around the start of the annual "border war" game between Colorado State University and the University of Wyoming. The two schools have faced off each fall since 1899.

"This is the highway to get between Fort Collins and Laramie," Werner said, pointing to 287. "So we go back however many years we've been playing that game with the University of Wyoming and my guess is they probably started soon after that.

Northern Water doesn't mind people painting the rock. Werner said the organization doesn't even track when new messages appear. He's never seen anyone paint it.

"I'm guessing that most of the time when people are doing this is at night," he said.

Fun and games

It isn't easy to find people who will admit to trespassing on land to paint a rock. But I tried.

After dozens of calls to businesses and churches in the area and a last-ditch Twitter callout, Nick Korsick sent me a direct message.

He's 31 and lives in Denver. In the fall of 2006, he was a freshman at the University of Wyoming.

He told me that the night before the border game that year, he and a few other people in his dorm decided to paint the rock.

"We waited probably until 10 or 11," he said. "We made sure it was nice and dark."

They piled into two cars and drove more than 50 miles south. They pulled over on the gravel shoulder and hopped the barbed wire fence, spray paint in hand.

Korsick was the lookout.

"In curt 18-year-old style, we wrote 'expletive CSU,'" he said.

The football game was in Wyoming that year. So, Korsick and his friends knew hundreds of Rams fans would drive past Haystack Rock the next day, including his family.

When they arrived, Korsick knew they'd seen his message.

"They were complaining to me about all the rude Wyoming people that had painted on the rock," he said. "And I just kept my mouth shut because they were buying me dinner."

Wyoming won that year 24-0.

Korsick said the reason he thinks people keep painting the rock is because it's fun.

"Nobody's getting hurt," he said. "There's some easy trash talk. 'I was the one who painted the rock.' That kind thing."

As of publication, KUNC has not confirmed any new paintings for this year's game.

The two schools will face off for the coveted bronze boot on Nov. 22. It will be the 111th official border war game.

A sudden loss

Every so often, an artist paints something on Haystack Rock that goes beyond the rivalry between CSU and Wyoming.

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, someone painted an American flag on its surface. No one touched it for years, locals told me.

And earlier this year, Shelly Robinson's family became a part of that tradition.

In March, her father suddenly passed away after a routine medical procedure.

"My dad was a cowboy," Robinson said. "He loved the mountains."

Paul Brabson was also a family man, Robinson said. One time, when her son Alex was four, Robinson got a call from her dad. Alex was staying with him in Red Feather Lakes, where he lived.

"(My dad) was having chest pains and he got in his car with my son and was gonna drive to the hospital," Robinson said. "But he sat there in the car for a minute and thought, 'If I start down the mountain and something happens to me and Alex gets hurt, Shelly's gonna kill me.'"

So, Brabson got out of the car, went inside and dialed 911.

On the way to the hospital, Brabson went into cardiac arrest.

"He survived," Robinson said. "But still to this day, he would always say if it wasn't for Alex, he would have tried to drive himself to the hospital."

Shortly after his death, Robinson was driving up to the Red Feather Lakes area to plan her father's memorial service. Out the window, Alex, now in his 20s, saw Haystack Rock and got an idea.

"Alex was like, 'Oh my gosh! I remember passing that all the time to go to Papa's,'" Robinson said. "And what if I paint that so that when people come up, they'll be able to see it, you know, when they come up for the service?"

So, the day before the funeral, the family drove out to the remote stretch of road and painted two sides of the rock.

On one side, they wrote the words "R.I.P Paul." Underneath, they added his nickname "Bill," along with a big read heart.

On the other side, Alex painted a whole scene of the Rocky Mountains. A wooden cross with the dates "1943-2019." A cowboy hat. A pair of boots standing neatly at its base.

For Robinson, the public reaction to the mural was overwhelming.

"People that passed were honking," she said. "Just knowing that people were seeing that and hopefully stopping for a minute and saying a prayer or being thankful for something in their life that they may not have thought of if they wouldn't have seen something like that painted on the rock ... It was amazing."

Eight months later, the main mural is still intact.

Robinson said she was surprised to hear students hadn't covered it up yet.

"I think with the rock it's a moment in time you can capture," Robinson said. "Like the 9/11 tribute, the tribute to my dad, the birthday parties — all things that are important in someone's life at some time."

Uncertain future

There's a big question hanging over the rock's future. Will it be swallowed by a new reservoir?

The land where it sits is included in the Northern Integrated Supply Project, or NISP. The project aims to provide the region with adequate water supply as the population grows.

Glade Reservoir, one of the new reservoirs included in the plan, is set to flood the valley. Planning meetings are underway, but there's no start date yet for construction.

Brian Werner with Northern Water said the agency is weighing whether to move the rock ahead of construction.

"We're going to do everything we can," Werner said. "We've got a visitor center and it would be perfect to put in there."

Unfortunately, it's a heavy lift. The boulder weighs an estimated 40 tons.

To save it, Northern Water would have to hire several big trucks.

"Our engineers say it's not impossible but it's virtually impossible," Werner said. "I don't know if you blast it and try to piece it back together or you leave it at the bottom of the reservoir for future scuba divers."

Regardless of its fate, the rock will live on as an important part of life in Northern Colorado, Werner said.

"It was this big granite stone in the middle of nowhere," he said. "But as people started painting it, it's definitely become a cultural icon."