As the threat of wildfire grows, so too does the likelihood of mass evacuations. Perhaps no one knows this better than the survivors of last year’s Marshall Fire. While more than 37,000 people escaped the fire that day, the chaos that ensued prompted an overhaul of how these communities evacuate.

Erica Solove lived right at the edge of the Sagamore neighborhood in Superior. The entire neighborhood burned down in the Marshall Fire last year.

Solove called 911 when she saw heavy winds and smoke out her window. She said the dispatcher said they didn’t know anything about a fire in the area.

As she hung up the phone, Solove said she looked out the window and saw flames on her roof. She and her husband immediately jumped into action, grabbing their two kids and running out to the car.

“None of us were wearing shoes, no wallet. I mean that it was that quick,” Solove said.

There were so many close calls that day. Two people died in the fire, one of whom lived in Solove’s Sagamore neighborhood.

A few streets over, Solove’s neighbor Alie Hopper heard a police officer on her block telling people to evacuate over a loudspeaker. She grabbed her two small children and dog and ran out to the car in the driveway.

“My teeth had ash on them, the whites of my eyes, when I looked in the rear view mirror, like everything was just covered in soot,” Hopper said.

A lot has changed since the Marshall Fire, according to Steve Silbermann, communications director for the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office.

“I think we are way better off now in our community than we were prior to the Marshall fire,” Silbermann said. “And we learn more from each incident and we make changes from what we learned.”

‘We just hadn’t gotten there yet’

Some of the changes made to evacuation protocol were already in the works, but just hadn’t been completed yet. A prime example is the pre-designated evacuation zones, basically a plan for where to evacuate in case of emergency.

During and prior to the Marshall Fire, valuable time was spent drawing evacuation maps. The incident commander on the ground would call in an evacuation to a 911 dispatcher, and together they would decide the bounds of where to evacuate.

“It doesn't take a lot of time for the dispatcher to draw the shape, but when you have to interpret directions from someone in the field that's truly in a danger zone, it takes time to have that conversation,” Silbermann said.

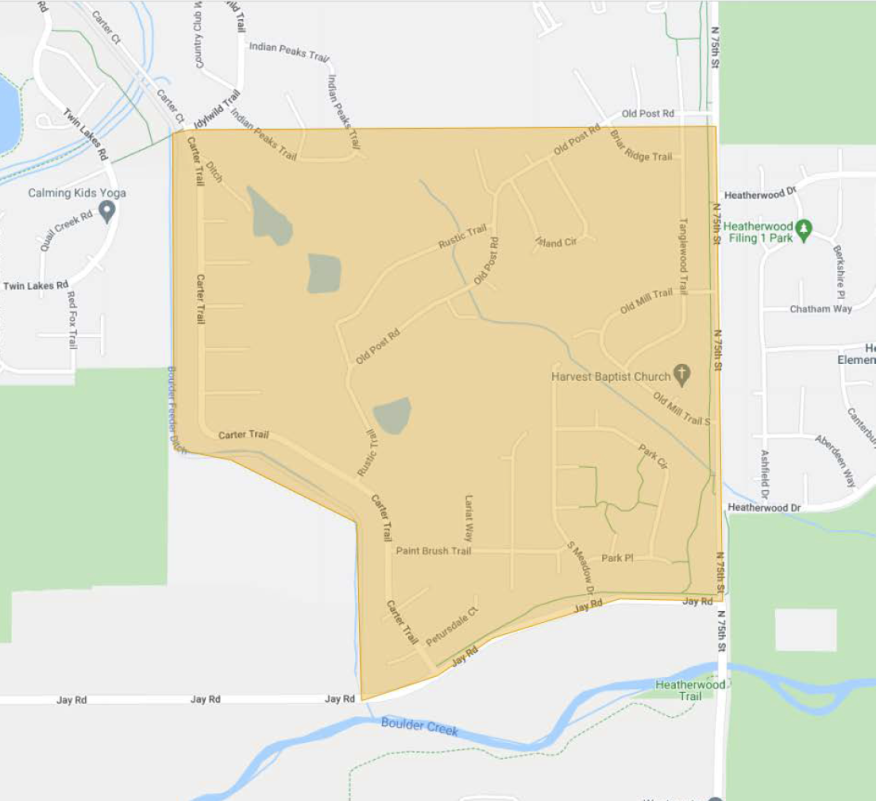

But not anymore. The Boulder County Sheriff’s Office finalized the new evacuation zones for the entire county in August, with help from local emergency responders in each municipality. That means emergency responders can call in an evacuation zone and 911 dispatchers will get moving on evacuation alerts right away.

Silbermann said the foothills already had these zones because that’s where the wildfires were historically.

“That wasn't to say we weren't gonna do it for the flats. We just hadn't gotten there yet,” he said.

‘Why didn’t anyone tell me?’

The county took a lot of heat from residents over emergency alerts in the months following the fire. Some said they took it as gospel that someone would warn them if they needed to get out. But many residents say they never got an alert the day of the fire.

This spring, the county launched a new emergency alert system that can send a message to all cellphones in an area, even to those who haven’t opted in to the emergency alert system or someone just passing through. It’s similar to an Amber Alert but for fire evacuations.

The county has also adopted a system that will broadcast alerts across the bottom of cable television screens and interrupt radio programming, much like a severe weather warning.

Better communication during emergencies

The county has also taken steps to better communicate with the public during an emergency.

Prior to the Marshall Fire, it would be hours into an emergency before the county would post a map of where evacuations had been ordered. This presented a challenge to Marshall fire evacuees, many of whom describe having little information on the scale of the fire or where it was heading.

Now though, Boulder’s Office of Emergency Management will post a map online that shows which neighborhoods have been told to evacuate during an emergency.

A link to this map will be included at the bottom of evacuation text and email alerts.

That means even if you haven’t received an alert or are not in an evacuation zone, you can still go online and see where evacuations have been ordered.

“We immediately can get better information in the hands of the people that really need to know,” Silbermann says.

‘Don’t wait for the alert to take action’

A review of the emergency response during the Marshall Fire found that “the fire was moving faster than some of the evacuation orders could be developed and launched.”

Mike Chard is the director of Boulder County’s Office of Emergency Management. He said that in a fast-moving emergency, the bottom line is that people need to be ready to evacuate without official warning.

“Don't wait for the alert to take action. If you see smoke, you smell smoke, you're worried you've got something on social media you're picking up – get out. Go to a place where it's safe and then figure out what's going on. Don't wait for the order to go.” Chard said.

In fact, that’s what many of the evacuees from the Marshall Fire did.

When Tawnya Somauroo saw smoke from her home in Louisville, she immediately started texting her neighbors and other moms to get out. There are a lot of these stories of neighbors helping neighbors that day.

“It's amazing no one in my neighborhood died,” Somauroo said. “It is such a blessing, but it's a stroke of luck. Now that we know this danger exists, it should never be such a close call again.”

For many of the survivors of the Marshall Fire, it’s not just about getting out alive. Somauroo and other residents say that a better evacuation process would have given them more time to make tough decisions – to grab a pet or a wedding ring, or even a pair of shoes.