Over the past decade or so, we've seen hurricanes pound the Gulf states. Of course foremost in the national consciousness is still Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall near New Orleans in 2005.

Not only that but if you exclude Florida, the last major hurricane — meaning category 3 or stronger — to make landfall in the Eastern Seaboard was Hurricane Fran, which made landfall in North Carolina in 1996. But during the past two decades, the Gulf Coast has seen Andrew in 1992, Opal in 1995, Bret in 1999, Charley and Ivan in 2004 and Katrina, Rita and Wilma in 2005.

The last major hurricane to hit New England was Gloria in 1985, which hit the Outer Banks, then made landfall in Long Island and then made a third landfall in Connecticut.

Needless to say, our memories of Atlantic hurricanes is a bit rusty. But Dr. Corene J. Matyas, a professor of geography at the University of Florida who specializes in the locations of hurricanes, says that could be because storm tracks develop patterns over decades.

She said some decades the Gulf states bear the brunt and others the Atlantic states do.

"Historically it shifts back and forth," she said. Matyas said a lot of it depends on where high pressure systems set up in the United States. Some hurricane seasons, high pressure systems will just sit on top of the Eastern Seaboard and all hurricanes are deflected to sea.

The problem, said Matyas, is that we can't really predict what pattern we'll be in or for that matter, we can't say we're in a pattern until we look at the past. She says meteorologists can predict level of activity but not likely path.

We looked at some historical data from the National Hurricane Center and what we found was that whether you remember it or not, the East Coast has been battered.

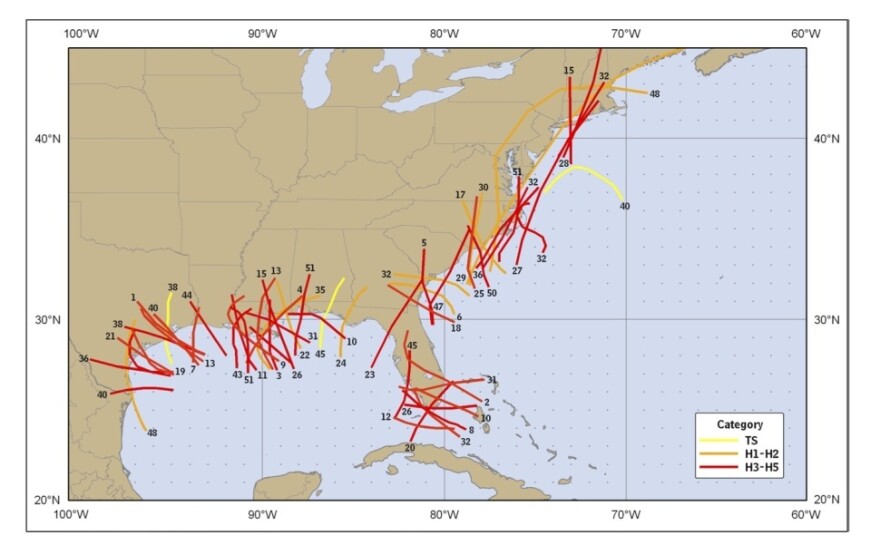

Look at, for example, this map:

It shows deadliest tropical cyclones in the United States from 1851 to 2010. Quite clearly, it shows that things are pretty evenly distributed.

Now look at this map:

It shows the costliest tropical cyclones to strike the United States since 1900. And here you do see that most of them are clustered in Gulf region.

But it also shows something to keep in mind: Sometimes even a category 2 hurricane can be costly. Number 12 on that map, which shows a track a lot like the one Irene is forecast to take, was Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Floyd, according to the Hurricane Center, dragged on from the mid-Atlantic to the Northeast United States and caused $6.9 billion in damages, yet made landfall in Cape Fear, North Carolina as a category 2 hurricane with top winds of 105 miles an hour.

Sean Burke, a senior fellow at the Center For National Policy, a Washington think tank that focuses on national infrastructure, said he didn't want to dismiss Gulf hurricanes, but those on the East Coast that drag on like that "affect more densely populated areas."

Burke says the problem is not that people in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast aren't used to hurricanes, it's that those areas are "least prepared" when it comes to infrastructure.

It's big things like New York City's subway system, which moves millions of people, but can't handle huge rains. Or the fact that New York City is on an island and built up hugging the shore. And it's also smaller things like tree canopy. In places like Connecticut, for example, which hasn't been hit by a hurricane in a long time, trees have had a chance to grow. When a storm hits those trees, said Burke, it can wreak havoc on the power lines and it can take quite a while to get electricity back up.

On the path that is projected for Irene right now, the storm will ride the East Coast and come very close to Manhattan. Perhaps not as close as Hurricane Agnes did in 1972 (5 miles) but it can certainly get close enough like Floyd did in 1999 (30 miles).

Nate Silver, the New York Times statistics guru, looked at historical data and came up with what a direct hit on New York City could cost.

The numbers are staggering. If a category 2 hurricane came within 50 miles of New York City, Silver estimates it could cost between $9 and $24 billion:

Which is all to say, Irene means serious business. President Obama made that clear today and Mayor Michael Bloomberg is treating it that way, too. Earlier today, Bloomberg ordered the evacuation of 250,000 New Yorkers. He said it's the first time that's ever been done.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))