COVID-19 testing facilities across the nation are experiencing backlogs and supply-chain shortages. One way to speed up testing and save resources is to pool samples, but the state testing lab at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is not.

There are some reasons behind the decision.

If most of the people getting tested are negative for COVID-19, a lab could save time and resources by pooling tests. The idea is you would combine 10 patients' samples and test them all at once. If the test comes back negative, you've saved time and reagents for nine tests. If it comes back positive, you need to go back to the original samples and test each individually, using 11 tests in total instead of 10.

Dr. Emily Travanty is the scientific director at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE). She says pooling works well when there aren't a huge number of positive cases, but, "once we get above 10% positive patients, we would expect all of the pools to then kind of come up positive."

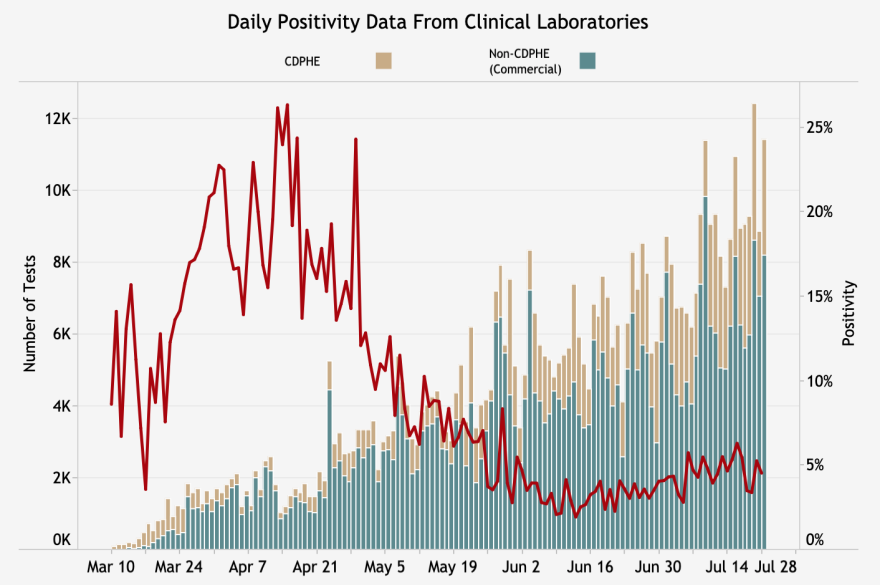

Right now, Colorado is seeing about 5% of tests come back positive. This so called " positivity rate" was over 10% for all of April and peaked at 26% in mid-April.

The practice of pooling samples only saves resources if your infection rate is lower than the number of samples you pool.

The bigger downside to pooling tests is that you may miss one — or get a false negative. The test amplifies tiny amounts of the viral genome. If you dilute a tiny amount by mixing it with the other samples, you may not detect a positive sample. Early on, the CDPHE tested this theory.

"We picked intentionally some samples that we had already run in the lab and we knew that they were very weak positives," said Travanty. She means that the samples had very little viral genetic material. "And we tested those in pools with known negative samples and we saw that once we started mixing more than two or three known negative samples in with a weak positive that we completely lost the signal."

The benefit of pooling samples is that pooling can help labs work through the incredible number of samples they're processing. If a patient is low-risk — maybe they live alone, work from home, and are asymptomatic — a false negative is not as much of a danger as someone who may be more likely to spread the virus.

The CDPHE's lab conducts about 30% of all testing in Colorado. They focus their efforts on testing higher-risk populations, like people in long-term care facilities, prisons and detention centers. Missing a positive case in a high-risk environment could have huge consequences. The state lab does not want to take this risk, so they're not pooling tests.

Labs nationwide are struggling to gather enough supplies to meet demand. Pooling can buffer supply chain issues with lab materials that are instrument-specific, like plastic tips or sample plates. Because the CDPHE isn't pooling, they're instead planning on shifting the workflow to use different instruments they can get supplies for.

"The state laboratory has worked to develop open systems that we can then pivot to what's available, but it does take time to stand up a different work-flow in the lab. We could experience temporary changes to our turn-around time as we have to pivot to different supply chains," said Travanty.

As new assays and materials become available, they're open to look into pooling again.

"As we're coming back around though to potential supply chain issues again, and there's new assays out there on the market, the concept of pooling is something that we would definitely like to investigate again," she said.

Unfortunately, there is a nationwide shortage of viral transport media, the liquid the sample goes into.

"It's an issue across the country. We get samples in from FEMA, we have some purchasing contracts to purchase it, but that is one of the difficulties," said Travanty.

This step can't be helped by pooling, because the tube of viral transport media identifies your sample among all others.

Testing is an important component of the state's coronavirus response. Without it, people are left wondering if they need to self-isolate or not. Daily testing has steadily increased since March. This curve has yet to "level off."

The CDPHE performs about a third of all tests in the state. As for the rest, Colorado has 50 community testing sites and private clinics . Many test asymptomatic patients.