When NASA's next Mars rover blasts off later this month, the car-sized robot will carry with it nearly eight pounds of a special kind of plutonium fuel that's in short supply.

NASA has relied on that fuel, called plutonium-238, to power robotic missions for five decades.

But with supplies running low, scientists who want the government to make more are finding that it sometimes seems easier to chart a course across the solar system than to navigate the budget process inside Washington, D.C.

Plutonium-238 gives off heat that can be converted to electricity in the cold, dark depths of space. It's not the same plutonium used for bombs. But during the Cold War, the United States did produce this highly toxic stuff in facilities that supported the nuclear weapons program — although those facilities stopped making it in the late 1980s.

"Because the United States has access to plutonium-238, we are the only country that has ever sent a science mission beyond Mars," says Len Dudzinski, the program executive for radioisotope power systems at NASA headquarters.

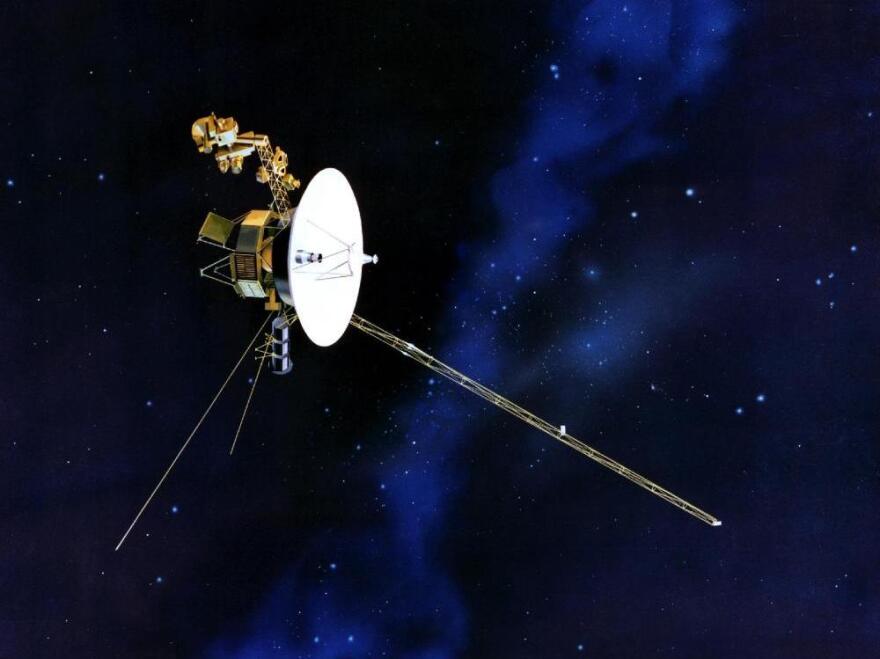

Dudzinski says NASA has used these plutonium-powered systems for famous missions like the Voyager probes. "In fact, we've got Voyager now with over 30 years of successful operation," he says. "It is the farthest man-made object from Earth that NASA has ever sent out."

Besides Voyager, plutonium fuels the Cassini probe, which is orbiting Saturn, as well as the New Horizons mission, which is headed to Pluto.

The pounds of plutonium loaded onto the soon-to-be-launched Mars Science Laboratory represent a significant fraction of a dwindling inventory. "I can't tell you exactly what that fraction is," says Dudzinski. "The Department of Energy knows the exact amount of plutonium that we have, and they don't ordinarily share that number publicly."

But the shortage is public knowledge and has been for years. For a while, Russia sold us some of the material, but that source has dried up, too. In 2009, a report from the National Research Council warned that the day of reckoning had arrived and that quick action was needed.

The Debate Over Cost-Sharing

Space exploration advocates point out that it will take years to get the plutonium production process started, so delays now could have consequences later.

Jim Adams, deputy director of planetary science at NASA, says that with budget pressure slowing the pace of exploration, there's enough of the fuel for NASA missions currently planned through the end of this decade, to around 2022. "Beyond that, we'll need more plutonium," he says.

If NASA doesn't get it, he says, "then we won't go beyond Mars anymore. We won't be exploring the solar system beyond Mars and the asteroid belt."

"It takes at least five years to get enough for one spacecraft," says Bethany Johns, a public policy expert with the American Astronomical Society who has been lobbying Congress on this issue. "So there's a long time between turning on the on switch at the facility and then actually producing enough that can be handled by humans to put into a spacecraft."

NASA has made some progress in helping the Department of Energy develop plans to restart production, says Adams. "We have worked with the Department of Energy to supply up to $5 million this fiscal year," he says.

But the agencies have run into trouble convincing Congress to accept their plan for how to deal with the costs.

The price to restart production is expected to be $75 million to $90 million over five years. And NASA and the Department of Energy want to split the bill between them. That's how they've done this sort of thing in the past, because even though NASA will use the plutonium, only the Department of Energy can make and handle this nuclear material.

But some key decision-makers don't like that cost-sharing idea. Lawmakers in Congress have refused to give the Department of Energy the requested funds for this project for three years in a row.

Earlier this year, Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., pleaded with his colleagues to reconsider during an appropriations committee meeting. "Does anyone in this room think that we don't need the plutonium-238? Does anyone not want to continue to do deep space missions?" Schiff asked. "Well, the Russians won't give it to us, and we don't have enough of it."

But others said if NASA wants the stuff, NASA should pick up the whole tab. They said putting half of it under Energy's budget would mean taking money away from other kinds of nuclear research.

Schiff argued that $733 million was being allocated to nuclear energy research and that dedicating $10 million for the plutonium project shouldn't be a big deal. "This has got to get done," Schiff urged. "All we're quibbling about here is whether it's paid for by NASA completely or it's paid for by DOE completely, and both agencies have said what makes sense is to split it down the middle."

But the majority of his colleagues were unconvinced. Given the opposition in Congress, officials say they need to rethink things and figure out how much NASA can legally pay for under the Atomic Energy Act.

As things stand, experts don't expect production of new plutonium to be fully up and running before 2020.

"Our perspective is, we don't really care where the money comes from, as long as we get the money," says Johns, "because we need to start immediately."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))