More than 100 agencies across Colorado have approval from the state to allow medics to use ketamine, an anesthetic, on people who show signs of what's often dubbed "excited delirium," a practice that is now drawing national criticism from anesthesiologists and psychiatrists. Yet emergency doctors across the country, including 25 in Colorado, are defending ketamine's use in cases where severely agitated people struggle against police, even when they are physically restrained.

A KUNC investigation finds that Colorado paramedics and emergency medical technicians have used ketamine 902 times in cases like these in the last two and a half years. That includes 180 times in the first half of this year.

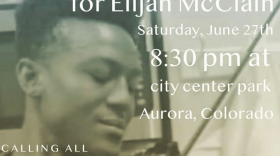

The disagreement among doctors comes amid renewed investigations into the death of 23-year-old Elijah McClain last year. McClain was wearing a ski mask and waving his arms, perhaps dancing, the night of Aug. 24, 2019 as he walked home in Aurora when officers approached him in response to a 911 call about someone appearing "sketchy." One officer told him he was "being suspicious" as he asked to be left alone, according to body camera footage.

Officers then grabbed McClain and claimed that he tried to grab one of their guns, and subdued him with a carotid hold that can cause unconsciousness. McClain pleaded with the officers, who claimed that he was combative and showed "incredible strength." An Aurora Fire Rescue medic arrived on the scene and gave McClain ketamine as he was in handcuffs.

In the ambulance, McClain suffered cardiac arrest and, three days later, was declared brain dead at a hospital and subsequently taken off life support. An autopsy concluded that McClain's cause of death was undetermined, but could not rule out the possibility that ketamine caused an unexpected reaction.

McClain's story has sparked Black Lives Matter protests and national interest and outrage amid new investigations at the local, state and federal level.

At the same time, emergency doctors from major cities around the United States — from New York City to Anchorage — are defending the use of ketamine to rapidly sedate people in incidents like the one with McClain involving law enforcement officials. A letter dated late last month states that ketamine used in such circumstances is meant to "safeguard the patients, while also reducing the risk of violence directed against EMS and public safety workers." Twenty-five Colorado doctors signed a separate letter earlier this month stating support for the national letter, including Eric Hill, who oversees Aurora Fire Rescue's ketamine program.

Hill declined KUNC's request for an interview through a fire spokesperson.

Dr. Kevin Mcvaney, the medical director for Denver's Emergency Medical Response System, also signed the letter.

"Excited delirium or agitated delirium is a condition where, due to a mental health problem, drug ingestion, some other physiologic and metabolic things, can make you just lose control and you're resisting, and you don't follow the normal stimulus that would make you stop resisting," McVaney said. "So you essentially can exercise yourself to death."

McVaney oversees medics in Denver who use ketamine in cases of excited delirium. His comments are in general and not specific to the McClain case.

Colorado emergency doctors stated in their letter that the use of ketamine as a sedative for extremely agitated people is "supported by the medical literature and by vast amounts of clinical experience."

That contrasts with guidance to the doctors by the state's Emergency Medical Practice Advisory Council. It states that ketamine use for excited delirium is an emerging treatment that "does not have a large body of evidence-based support in the literature."

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment has issued waivers allowing doctors to oversee 101 agencies that are approved to use ketamine for excited delirium. That includes agencies serving major cities, including Denver, Colorado Springs, Fort Collins and Greeley, along with many smaller communities.

The department, which declined to comment for this story, did not provide a breakdown of how many times specific agencies used ketamine in excited delirium cases.

KUNC also discovered problems in the 902 cases in the last two and a half years, including complications almost 17% of the time, according to an aggregation of medic reports. The most common was hypoxia, a severe lack of oxygen that is potentially life-threatening. That was a problem for more than one in 10 people given ketamine for excited delirium. Apnea, a temporary lapse in breathing, was an issue in two dozen of the cases.

Once people got to the hospital, there were intubations. That's when a tube is inserted in a person's mouth and they are placed on a ventilator to help them breathe. This occurred in about one in five recent cases of ketamine administration documented in a separate analysis of hospital data by state health officials.

These figures come to light amid a pandemic in which patients with the most severe cases of COVID-19 are also intubated, battling the effects of hypoxia, in hospitals with limited numbers of ventilators.

Asked if the McClain case has given pause to Aurora Fire Rescue's ketamine program, a spokesperson said it remains part of the "medical protocol."

Some doctors are voicing concern about ketamine's use in what are called "pre-hospital" situations, like the one involving McClain. That includes doctors with the Illinois-based American Society of Anesthesiologists. In a statement issued last week, the society said it "firmly opposes the use of ketamine or any other sedative/hypnotic agent to chemically incapacitate someone for a law enforcement purpose and not for a legitimate medical reason."

"Ketamine is a potent analgesic, sedative and general anesthetic agent which can elevate blood pressure and heart rate, and can lead to confusion, agitation, delirium, and hallucinations," the statement added. "These effects can end in death when administered in a non-health care setting without appropriately trained medical personnel and necessary equipment."

Dr. Karsten Bartels, an associate professor specializing in anesthesiology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, said ketamine's use in hospitals is well-established. It must be administered with caution, Bartels added, and an understanding of the patient.

"One has to take into account, for example, what the patient's baseline status is," Bartels said. "If you have a patient who maybe takes a stimulant as a prescription medication or if somebody has taken illicit stimulants, such as cocaine or amphetamines or something like that, then the side-effect profile of ketamine would be very undesirable."

In other words, if not used properly, ketamine can be dangerous to patients.

When McClain was given ketamine, first responders were using flashlights to see. The McClain family's lawyer — Mari Newman of the Killmer, Lane & Newman firm in Denver — said McClain received a "massive overdose that was designed for somebody so much larger than he was."

McClain should have received about 315 milligrams of ketamine because he weighed roughly 140 pounds, but medics estimating his weight injected him with 500 milligrams, enough for a person of about 220 pounds.

But while ketamine may have been a factor in McClain's death, the autopsy reported a "most likely" factor was his agitated state — excited delirium.

Newman disputes that McClain was violently struggling, as officials have said, or showing any signs of excited delirium.

"Any person who is seized by officers as they're walking home, just listening to music, minding their own business — of course, a person will tense up," she said. "Of course, a person will be surprised. … So I suppose one could say that the officers contributed to his agitated state, but he was not agitated. He actually was entirely compliant the entire time."

She points to body camera audio where McClain can be heard stating things like, "please respect my boundaries" and "I was just going home."

"Those are not the statements of somebody who is fighting," she said. "Those are the statements of somebody who was trying to survive."

The American College of Emergency Physicians, which represents 38,000 doctors around the country, has recognized excited delirium as a syndrome for more than a decade, but psychiatrist Paul Applebaum said it is not a mental disorder.

"To date, we have not been aware that there exists sufficient data to validate it as a diagnostic entity," he said.

Applebaum, with the Washington D.C.-based American Psychiatric Association, chairs the steering committee for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, otherwise known as the DSM, which determines psychiatric diagnoses. Excited delirium is not in the manual.

"It's at least worthy of asking, 'Why is it only in police encounters that (excited delirium) occurs, and then usually applied only when there's been a bad outcome?'" -Paul Applebaum, psychiatrist

"If excited delirium was a real and discrete diagnostic category, one would tend to see it arise in other places, and other circumstances," he said. "It's at least worthy of asking, 'Why is it only in police encounters that this occurs, and then usually applied only when there's been a bad outcome?'"

Colorado's guidelines on ketamine for excited delirium emphasize that emergency medical service providers "should not engage in restraining people for law-enforcement purposes." Applebaum noted that people who are given ketamine for supposed excited delirium are not likely to consent to it.

"It all leaves me uncomfortable," he said. "I have concerns about the use of drugs for purposes of restraints in general."