As the impacts of climate change worsen, many are turning their attention to methane, a harmful greenhouse gas. Scientists estimate methane is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide. President Joe Biden and other global leaders have promised to cut 30% of methane emissions by 2030.

Pitkin County is working with a group of stakeholders to capture a large amount of methane that has been leaking out of abandoned coal mines in an area known as Coal Basin above the town of Redstone. The area is about 45 road miles from Aspen and within Pitkin County.

In late September, representatives from Pitkin County, Holy Cross Energy and U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet’s office, and others hiked nearly 9 miles through golden aspen groves to witness the problem firsthand.

Paonia-based climate scientist Chris Caskey crouched in front of an old mine portal in Coal Basin that has been filled in with rocks and dirt. He uses a methane sensor to show the group where a steady stream of air and methane is leaking from a small hole in the porous earth.

“You can see those little wild roses are blowing in the breeze,” Caskey said. “That breeze is mostly air that's entering down lower and coming up through, but we measured it earlier. It's almost 2% methane by volume.”

A long history of coal mining above the town of Redstone

Coal Basin was once dominated by coal mines first opened by coal baron John Osgood in the late 1800s and were later redeveloped by the Mid-Continent Coal and Coke Co. in 1956.

“This coal was saturated with natural gas, mostly methane, and that's just for geology reasons,” Caskey said. “That methane is a minor safety hazard, so during mining, it was vented to protect the miners, and that methane has continued to leak out ever since.”

When the last of the five mines shut down in the early 1990s, the mining company was mandated to restore the area, but it went bankrupt and left behind polluted water and a scarred landscape.

Over the past several years, local stakeholders, including private landowners and Pitkin County Open Space and Trails, restored parts of Coal Basin and created a public trail system and a recreation area called Coal Basin Ranch.

Pitkin County incorporates methane capture into its climate goals

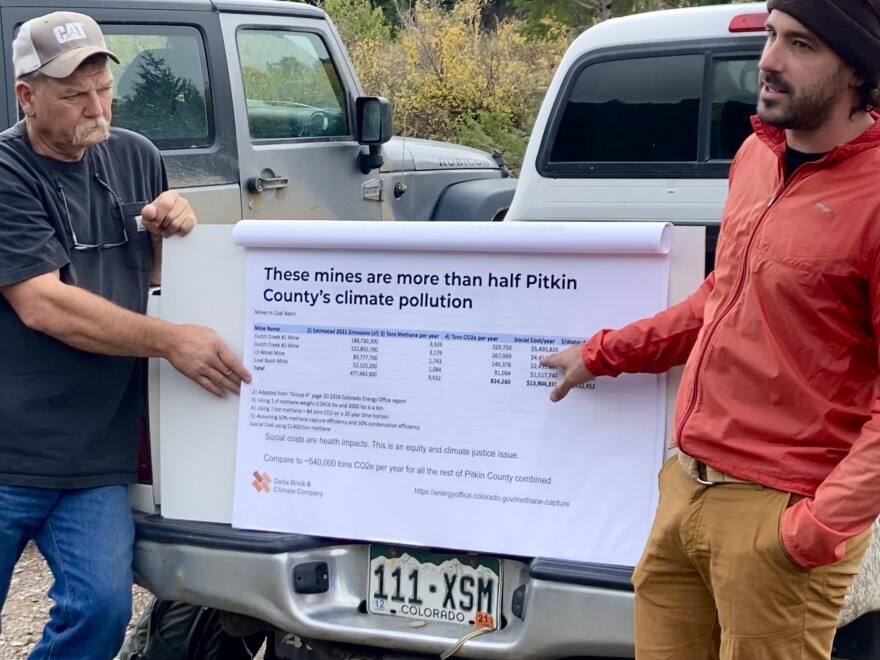

Despite restoration efforts over the years, Caskey estimates that the old mines are leaking more than a million cubic feet of methane daily. According to local officials, that’s equivalent to more than half of Pitkin County’s reported carbon dioxide emissions each year.

“That includes all the traffic, all the houses, all the aircraft landing at the Aspen airport,” Caskey said. “And Pitkin County being wealthy is not a low footprint place.”

According to Caskey, the methane seeping out of the mines isn’t concentrated enough to impact hikers or mountain bikers, but it is making its way into the atmosphere and contributing to climate change.

“So this is very significant and it's a huge opportunity to reduce climate pollution,” he said. “If we can capture this gas and either use it or just destroy it by burning it, that is a very good thing to do.”

For Pitkin County Commissioner Greg Poschman, the expedition up to the old mines made clear the benefits of taking action.

“This might be the easiest way to get a huge bang for our buck to reach our carbon goals, certainly by 2030, if not sooner,” he said.

Climate scientist and local stakeholders brainstorm solutions

According to Caskey, the cheapest solution for the stakeholder group would be to burn the methane, which creates carbon dioxide instead.

“And that really looks like wasting it,” Caskey said. “But right now, it's already being wasted, and CO2 is less bad for the atmosphere than methane.”

Another option being considered by the group is using the gas leaking out of the mines to generate electricity.

“Do we want to have a small power plant and have a microgrid here in the Crystal River valley?” Caskey said. “Or do we want to put it in a pipeline and run it to every house in Redstone? These are all possibilities.”

In addition to CO2, burning methane also creates steam, which Caskey said can be condensed into water that could then be released back into the local watershed.

“We can make a thousand gallons of liquid water a day,” he said. “That's not a lot from a stream-flow perspective, but there's no new sources and we're in a drought.”

In all of these scenarios, CO2 would still be released into the atmosphere, but Caskey claims that there is no viable way around that.

“If you give me another 2 million bucks, I can capture that CO2 and we can figure out something to do with it,” he said. “But for that same 2 million bucks, it'd be better to go capture methane from another coal mine because it's quite inexpensive compared to the impact.”

Interest in using methane from abandoned coal mines to generate electricity has been growing in recent years, but it’s still a novel idea. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, there were only two projects of this kind in the country as of 2019.

In 2012, Caskey worked with several partners, including the Aspen Skiing Co., to build a methane-capture plant at the Elk Creek coal mine in the town of Somerset.

The plant feeds the regional power grid and produces enough electricity to power about 2,000 homes. Caskey estimates the methane at Coal Basin could generate about the same amount of electricity.

Local stakeholders seek federal government approval

Although there is much to be learned from the Somerset methane-capture project, Coal Basin comes with a unique set of challenges.

The mining area is located on a mix of Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and private land, which means Pitkin County will need to get permission from individual landowners and the federal government.

“A coal mine that's abandoned and polluting the climate is not something that they have a framework for how to deal with,” Caskey said.

Mona Newton is the former executive director of the Aspen-based Community Office for Resource Efficiency and is now a consultant on the project with Caskey. She and the stakeholder group have sent letters to state and federal officials asking for their support.

Even with the many bureaucratic hoops, Newton thinks the project is doable now that the Biden administration is in power.

“With the previous presidential administration, there really wasn't any impetus to work on projects like Coal Basin that will tackle climate change,” Newton said.

The road ahead for Coal Basin

In addition to getting federal approval, the stakeholders are also looking at whether building a methane-capture plant will disturb local flora and fauna.

Despite some successful restoration efforts in the area, Pitkin County Commissioner Greg Poschman points out that there are remnants of the coal-mining days all around, and Coal Basin is not a pristine environment.

According to Poschman, the engineers hope to minimize construction by using the old power lines and mining roads that still zigzag up the mountainside.

“I'm not the guy you come to when you want to reopen a part of the backcountry to heavy trucks and equipment,” he said. “But the infrastructure is in place. There's no perceived environmental damage.”

For Pitkin County Commissioner Steve Child, the positive impact that the project would have on the climate outweighs the environmental impacts of building a small power plant in Coal Basin.

“Our winters now are at least a month shorter, if not more, than they used to be,” he said. “So our area really is in jeopardy of just surviving, and we rightfully are concerned about climate change.”

Newton agrees, but she also said that the methane-mitigation project shouldn’t be used as an excuse for Pitkin County to keep polluting the atmosphere.

“We can't stop working on the emissions that are generated within Pitkin County,” she said. “But this will go a long way towards helping to preserve our climate.”

If the project gets approved, construction could start as soon as next year.

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a collaborative reporting project with Rocky Mountain Community Radio looking at fossil fuel transitions in the West.

Copyright 2022 Aspen Public Radio . To see more, visit Aspen Public Radio . 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))