Bradley Cheetham was about to deliver his fourth or fifth presentation in one month. He’d given so many, he said, he’d nearly lost track.

Pacing back and forth in the hallway outside the Colorado School of Mines classroom, where a crowd of space industry bigwigs awaited him, he shared a few words about life as an entrepreneur.

“Honestly, entrepreneurship is a really hard job,” he said, laughing. “Space is a really hard job. Doing them together does not make either easier.”

Cheetham runs a company called Advanced Space. He started it with three friends in 2011 as a graduate student at the University of Colorado Boulder. The company’s first headquarters was the upstairs loft of his apartment at the time.

Since then, it has grown into a promising force within Colorado’s booming aerospace industry.

A team of 15 employees works at the company’s modern (non-loft) office in Boulder, building and selling its space mission services. They range from launch targeting to program development and navigation design.

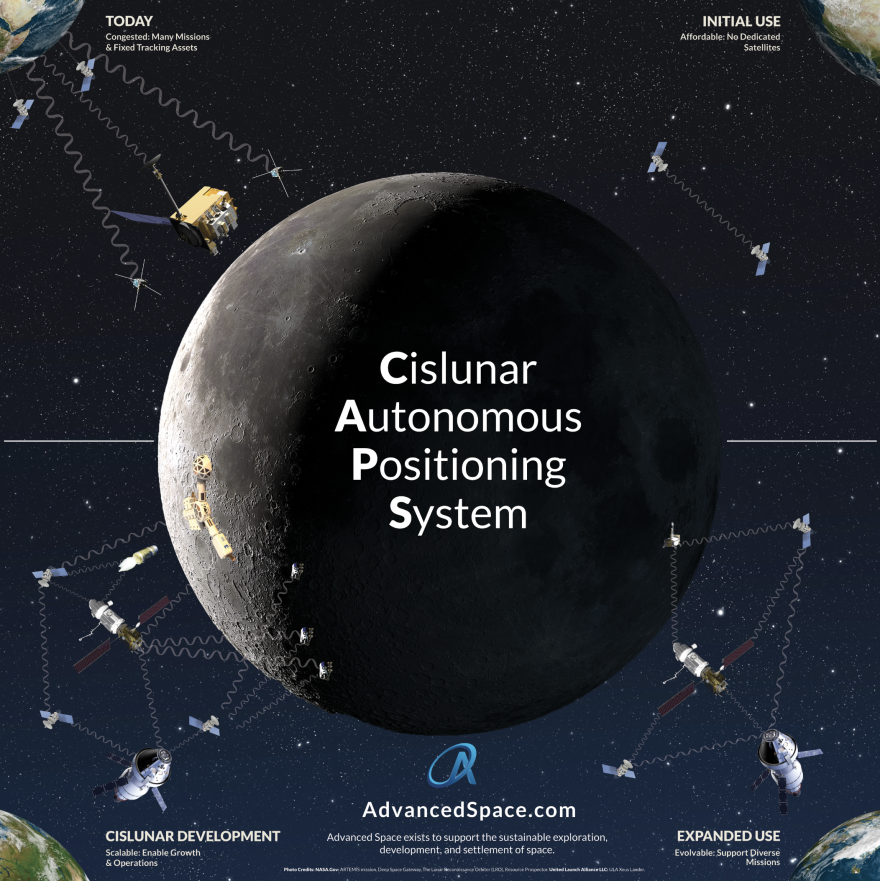

Right now, he’s focused on touting the company’s new spacecraft navigation technology, the cislunar autonomous positioning system, or CAPS. Think of it as the GPS on your phone or car, but for rockets and satellites to talk to each other.

Today’s spacecraft depend exclusively on communication with contacts on Earth to move through the galaxy safely. These systems are tightly scheduled and in high demand, Cheetham said.

The bottleneck of communication is putting a strain on NASA and other countries’ space agencies, according to Cheetham.

It gives companies like Advanced Space an opportunity to do business.

In the past year, the company has secured at least two new NASA small business contracts, each worth more than $100,000. In May Colorado’s Office of Economic Development and International Trade gave it $250,000 as a part of its advanced industries program.

Advanced Space does not launch its own rockets. Testing CAPS involves partnering with other companies and space agencies who do, which is why every pitch he delivers matters.

“We’re new,” Cheetham said. “And they’re not going to wait for us. We have to be ready to fly when those missions need it.”

He walked into the classroom at the School of Mines, ready to make his case.

A growing industry

In Colorado the aerospace industry directly employs nearly 30,000 workers, each of them solving space-related problems that may sound like something out of a sci-fi film. And it’s growing – fast.

Jay Lindell, who works state’s Office of Economic Development and Trade as the aerospace champion, said the industry expanded by 4.7 percent last year.

“When you get economic growth above 3 percent, you’re doing really well,” he said.

Through economic analysis the state has determined the industry indirectly employs nearly 190,000 people, a lot of which is in software development.

The bulk of employment comes from big companies like Lockheed Martin and United Launch Alliance, said Lindell. But most of the innovation comes from smaller companies that support them, like Advanced Space.

“They’re really the catalyst of this industry sector,” he said. “You find the most passionate business leaders. It’s amazing how hard they work.”

Lindell credits NASA with driving the industry’s growth. In March the agency announced an ambitious plan to increase missions to and around the moon — the first of which could come as soon as 2022.

To make that happen, the agency will leverage public-private partnerships, among other things, to fast-track space exploration missions, according to its fiscal year 2019 budget proposal.

At an event with potential commercial partners held in May, Jim Bridenstine, a NASA administrator and former congressman, triumphantly declared the return.

“We are going to the moon!” he announced to an applauding crowd.

President Donald Trump nominated Bridenstine to the post in September 2017. Since then, the new administrator has made partnering with private industry a top priority.

“This will help us conduct more missions. More exploration. More prospecting and more science to learn more about our nearest neighbor,” Bridenstine said.

Lindell says the potential opportunities are a goldmine for companies like Advanced Space.

Moving forward

Cheetham keeps a few special items on his work desk to keep him in line with one of the company’s key philosophies.

“We respect the past here,” he said. “We want to really recognize how we got to where we are.”

There’s a picture of Dr. George Born, the famous NASA engineer, riding a tractor on his family’s farm in Texas.

Born served as Cheetham’s PhD advisor at CU Boulder and was a big influence on the aspiring engineer, he said. Born died two years ago.

“He was always a major technical advisor, and for me personally, as a career,” Cheetham said. “He’s a big reason why Advanced Space is what it is.”

There’s also a photo of Darrell Cain, smiling. Cain was one of the company’s original co-founders. Shortly after the company's foudning, Cain was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Cheetham said Cain lost his battle with the disease in 2012.

He and Cain met when they were both undergraduate students and began planning the foundations of a space company shortly after. Cain had a big personality, Cheetham said.

“We didn’t know exactly what we were going to do,” he said. “He helped us get (the company) started.”

The company’s other co-founder has since left Advanced Space.

Cheetham and another co-founder, Jeffrey Parker, remain involved with the business. Parker as chief technology officer, Cheetham as president and chief executive officer.

In his engineering lab, Cheetham demonstrates how CAPS works.

On a table, he places three black boxes, each about the size of a portable hard drive. They’re hooked up to computer monitors displaying dozens of lines of code. Each of the boxes represents a rocket or satellite orbiting the moon.

“In here, we can simulate what not just one spacecraft running this software would look like, but what happens if you have three,” he said. “And they have different inputs and outputs and they’re talking to each other.”

The system is mainly software, but Cheetham’s next goal is to make sure CAPS’s hardware takes up as little physical space on a satellite or rocket as possible. That would make it easy to add to the insides of an existing spacecraft.

The new grants from the state and NASA contracts will help him do just that, he said.

But even with the money, Cheetham said, the ultimate success of CAPS depends on testing it in space sometime in the next few years. That way, larger lunar missions can use it.

“We’re focused on getting this ready to go, so that as many missions as possible can start to use it,” he said. “Then it will continue to get better and better.”

With the help of the state and his scrappy staff in Boulder, Cheetham says he’s sure he will be ready to fly.