On May 19, 2018, Charles Battle II was feeling great. The 17-year-old had spent the day with his girlfriend at the Five Points Jazz Festival near downtown Denver.

“Then went back to her place. Hung out for a little while,” he said.

Trying to get home before his curfew, he left around 10 p.m. and got on a city bus for the journey back to his parents’ house in Far Northeast Denver. Battle transferred to a second bus before getting off and walking the rest of the way. A sudden bright light stopped him.

“I got picked up by the cops,” Battle said.

Body camera footage from the Denver Police Department shows Battle, who is Black, with his hands in the air, obeying the police officers’ commands.

“Hey, keep your hands up. Walk towards me,” said an officer. “Stop right there. Hey man, drop down to your knees.”

Battle is wearing black shoes, black jeans and a black coat with gray sleeves and a gray hood.

“Set your phone down, interlace your fingers behind your head,” the officer continued.

Three officers approach him. He’s handcuffed and put in the back of one of four police cars on scene. Two other officers are standing by.

“I'm at that time, see that they had guns pointed at me,” said Battle. “I thought I was going to die right there.”

About 30 minutes earlier, in a nearby neighborhood, a Hispanic woman saw two men in gray sweatpants and hoodies attempting to steal her husband’s truck. When she approached, they chased her with a small knife and then fled. She speaks Spanish, so her daughter called 911 and described what happened.

“I need a description of them,” said the 911 dispatcher. “What race were they?”

“They were Black,” replied the daughter.

Once Battle is in custody, a police officer picks up the eyewitness and drives her to his location. When she arrives, another officer takes Battle out of the police car. Still handcuffed, he’s placed where she can see him from the backseat. She identifies him as one of the perpetrators. At that moment, Charles Battle II, who had never been in trouble with the law, was going to jail.

“Now you're under arrest,” said an officer.

Battle was arrested because of a showup. It’s a form of identification where a witness is shown only one suspect close to where the crime occurred. It differs from the other types of lineups that have several people to choose from and are usually done at a police station.

Showup identifications are conducted at the discretion of law enforcement.

“I guess it would really depend on your jurisdiction and what is going on,” said Michael Phibbs, the chief of police for Auraria Campus.

Phibbs has been a police officer for 30 years. He rarely used showups when he was working in Summit County and only occasionally while chief of police for the town of Elizabeth. There, he said, victims of crime often knew their perpetrators, and suspects were easier to find. But in an urban area like Auraria campus, people are more transient. A showup is helpful for crimes like theft or assault.

“We actually use it fairly often because we have a lot of calls that involve people who are moving quickly,” he said. “If we don't briefly detain them to make sure we're talking to the right or wrong person, they can easily be gone.”

But opponents say this practice can be manipulated by law enforcement. Suspects might be commanded to say something or walk in a certain way. Or like in Battle’s case, be in handcuffs while they are identified. An eyewitness may also feel pressure from officers to positively identify a suspect.

“It is inherently suggestive,” said Rebecca Brown, director of policy for the Innocence Project. “You know, you're presenting one image and only one person, right, to another person. There are no other options. It’s an up or down.”

Showups should be used sparingly, she said, and are most effective at eliminating a person who matches the description of the suspect.

"I don't believe that it really delivers the kind of accurate and reliable identification that we want,” she said.

Another issue is cross-racial identifications. Research shows that racial groups are not good at identifying people of other groups. For example, the Hispanic woman who identified Battle, who is Black.

“To me, it's a recipe for disaster,” she said. “To have both an inherently suggestive procedure coupled with what we know about the fact that people are not good at identifying other racial groups.”

These procedures can also lead to misidentifications, which happens more often than people think. The Innocence Project has a dataset with 375 DNA-based exonerations in the U.S. and 69% of them involved at least one eyewitness misidentification. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, mistaken witness IDs contributed to 28% of exonerations.

“The truth of the matter is people get it wrong all the time,” Brown said.

In 2015, a law was put on the books in Colorado requiring law enforcement agencies to adopt policies related to best practices for showups. But there was no enforcement or oversight. The law also didn’t ask agencies to track how often they used the practice.

The search for Charles Battle II

Charles Battle was arrested for attempted aggravated robbery at 11:46 p.m. His parents, who were expecting him home by 10:30 p.m., were frantic.

“I was very upset,” said Sharon Battle, his mom. “I had no idea what had happened, and he wasn't answering his phone and I was calling over and over and over again. Just nonstop."

Sharon Battle and her husband were able to follow his movements via an app that tracked his phone. They saw it moving around in various parts of the city for several hours. His father even went downtown to look for him, but had no luck and returned home.

“The later it got it's like, you're a Black mom. You think about what you see on TV. You think about the stories you hear from other family members. You think about other kids who've had encounters with the police. You think about other community members that have had that,” she said. “So, your mind is all over the place.”

Then at 2:45 a.m. the police called her husband. Their son was being held at Gilliam Youth Services Center in downtown Denver.

“It was actually a relief when the call came in to say, you know, that he had been arrested. And he talked to his father. I could hear him talking to his father and I'm like, ‘OK, he's alive,’" she said.

They finally got to see him the next day.

“He just said, ‘Mom and Dad, I didn't do this,’ and we said, ‘OK,’” she said.

Charles Battle was released into his parents’ custody and then graduated from high school about a week later. He was offered a plea deal and a chance to go to a diversion program several times. He repeatedly turned them down because going to a program would be an admission of guilt.

“Once you're in that system and then once you get accustomed to being in it, it's hard to get out of. I have family that's had that experience,” Sharon Battle said. “It's a huge deal to be accused of a crime and then agree to it.

If convicted, he faced up to six years in prison.

Let’s change the law

Sharon Battle is a mom, first and foremost. She’s also an Air Force veteran, pastor and pastor’s wife. Add to that list, a volunteer activist and board member with Together Colorado, a non-partisan, multi-racial, multi-faith community organization with congregations across the state.

The Monday after her son was arrested, she attended a leadership meeting for Together Colorado.

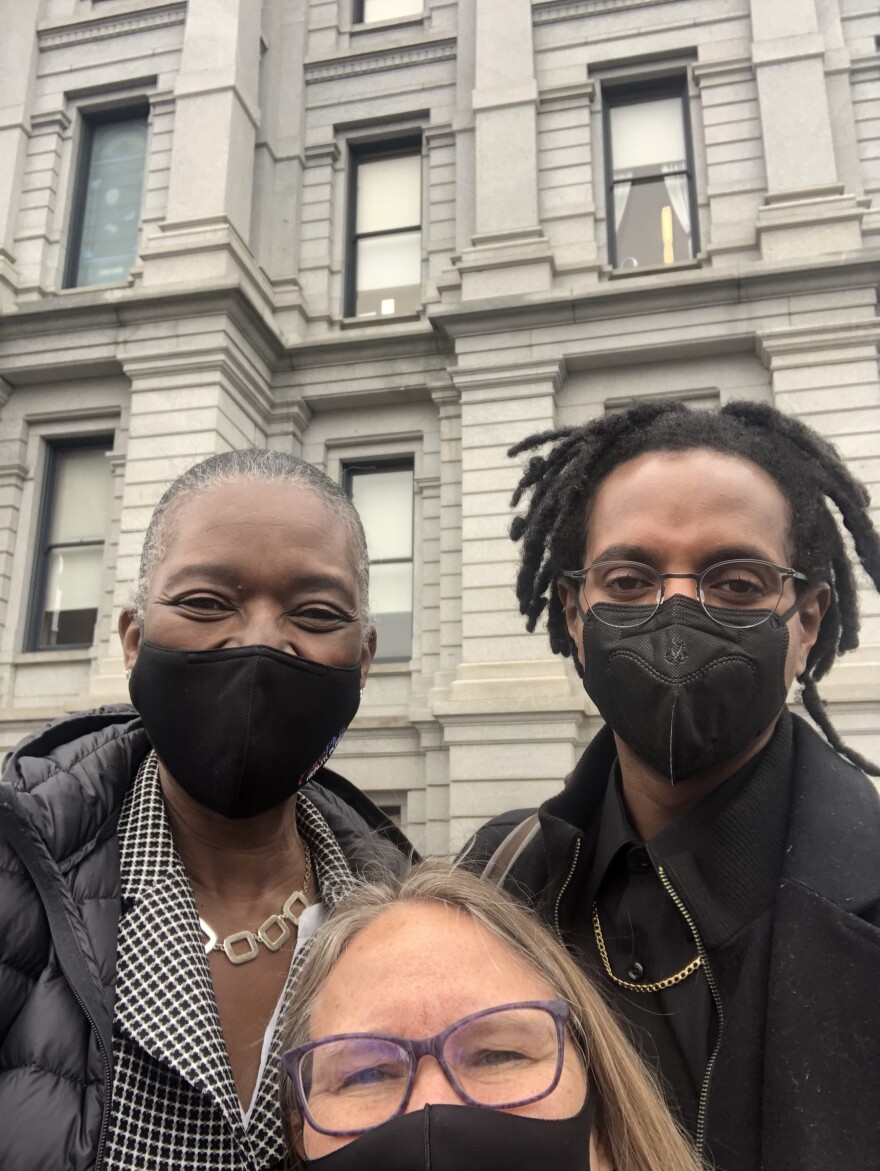

“Sharon comes in and she's real quiet,” said Kamau Allen, lead organizer with Abolish Slavery National Network.

In 2018, the 27-year-old was a community organizer with Together Colorado. Sharon Battle finally spoke up near the end of the meeting and shared what happened to her son. Everybody got so quiet you could hear a pin drop, said Allen.

“I said that he should be able to walk down the street and not be arrested,” said Sharon Battle. “He should be able to be comfortable in his own skin, in his own neighborhood.”

Together Colorado members include 220 Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Christian, Muslim and other congregations. But most of the people involved are white.

“I challenged the white people in the group to do something about this because white people in this country are still the people who are in power,” she said. “If they don't see it and do something about it and bring others into the mix. It's not going to change.”

Allen was one of the only young Black men working at Together Colorado at that time. He too had had negative experiences with the police and his uncle served 21 years for a crime he didn’t commit. So, he could relate on a deeper level.

“It was traumatizing,” he said. “It brought up to me a reminder that I'm not safe. You know, walking, driving.”

At Sharon Battle’s urging, Together Colorado got to work. They packed the courtroom at the pretrial hearings, asked people write letters to the Denver District Attorney and raised money for legal fees.

“Our number one goal right then and there was make sure that these cases are dropped,” Allen said. “And to do everything that we can.”

Their efforts, and the work of Charles Battle's lawyer, paid off. The case was dismissed without prejudice six months later. But that meant charges could still be refiled.

“If I have any other police contact, they can always bring this up right out of the dirt and I'm right back in the same spot,” Charles Battle said.

Before the arrest, he had planned to go to college and get a business degree. He hopped back on that path and enrolled at a local community college, but it only lasted a semester.

“I was depressed, I couldn't handle the course load. I was going through a lot,” he said. “I didn't see the point, you know. I just wasn't motivated anymore.”

Sharon Battle was thankful to God her son was alive.

“But so many sons and daughters are put in the position of facing this criminal system and being swept up in this pipeline every day,” she said. “The things that happened to Charles Battle II happened to thousands and thousands more people every day.”

However, this is not the end of Charles Battle’s story. A local lawmaker told Together Colorado they had two options: sue the Denver Police Department or change the law.

They decided to change the law.

Working together for change

Marilynn Ackerman is a retired social worker and librarian and a volunteer activist and leader with Together Colorado and its transforming justice team.

“We are trying to transform the justice system to be fair and equitable for all on all sides of the law,” she said.

Together Colorado has worked on legislative and community issues in the past. This includes a 2018 amendment to the state constitution that abolished slavery as a punishment for crime, as well as paid family leave and payday loan bills. But showups would be different — the organization took the lead on creating the new legislation.

“Lot of people think we have law backgrounds and research backgrounds, and we did not,” Ackerman said. “We are self-taught. We are self-motivated. We are community-oriented.”

One of Together Colorado’s first actions was a community organizing event at Shorter Community AME Church, the oldest Black church in the state. Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen was invited to answer questions in front of the diverse 600-person crowd. They expected him to say no to their demands, said Ackerman. But to their surprise, he said yes to them and agreed to work with the group.

“I think we engaged in meaningful conversation and dialogue showing what the issues and challenges were,” Pazen said.

Initially, Together Colorado wanted showups to be abolished, but that wasn’t realistic. So, they pivoted and decided to reform how police conduct them. The Denver Police Department got on board and implemented new trainings and policies. In December 2020, the department became the first agency in the country to collect data on showups. As of November 2021, DPD had conducted 83 of them.

The goal was to remove subjectivity, said Pazen.

“We don't want to ever contribute to an innocent person being unfairly arrested or prosecuted. We want to make sure that we are arresting the right people,” he said.

The Colorado Attorney General’s office oversees the Colorado Peace Officer Standards and Training. They partnered with Pazen and the Mesa County Sheriff’s Office to develop training for non-biased witness identification procedures, including showups.

“It's critical that we change the culture, so officers aren't finding themselves resorting to such tactics that are fundamentally unfair to anyone accused,” said Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser.

The Attorney General's office also worked closely with Together Colorado. The group was happy with the progress being made, but their focus remained the same: get legislation passed so all law enforcement agencies had to adopt these policies.

“The legislative process that they led is unlike anything I’d seen before,” Weiser said. "It's a model for citizen leadership, for servant leadership because they held conversations with all stakeholders. They listened. They asked questions. They were thoughtful. They were creative.”

Vickie Wilhite attends Shorter Community AME Church and is a social justice activist and community organizer with Together Colorado. One secret to the group’s success, she said, is they begin conversations talking about values, not a problem.

“At the end of the day, we all just want to make it home safely to our families. I can start just with that,” she said. “And that's the value that we all can get on board with.”

Wilhite is also the team’s data analysis expert. She tapped into their network of congregations and gave virtual presentations about showups to houses of worship statewide.

She customized presentations for specific religions, but all of them included a slide on the golden rule.

“Every religion has a golden rule,” she said. “It may sound a little differently, et cetera. But if we just could remember that and go by that, it would make a huge difference.”

Wilhite ended the presentations with a call to action, asking congregations to get involved and talk to their local lawmakers. The goal was to educate them and get congregants to support their legislation.

The creation of a bill

Democratic state Rep. Jennifer Bacon first heard about the arrest of Charles Battle from his mom, Sharon Battle. They are her constituents, but her support for the bill went beyond their family.

“I do represent Northeast Denver, but I represent African Americans across the state,” she said. “I represent low-income communities across the state.”

State data shows Black and brown people are disproportionately arrested in Colorado. As an attorney, Bacon understands the lasting impact the criminal justice system can have on people of color better than most legislators.

“I said, ‘this is a tagging system,’” she said. “This system, once you have a touch point with it, won't let you go. Even if you're cleared of it, now you have an arrest record and forget if you've even been convicted.”

An arrest record is a big, red flag. It’s always there when you apply for a job, an apartment or even an academic scholarship, Bacon said.

“This is an incredible injustice,” she said. “That is not what the criminal justice system is supposed to be.”

The Eyewitness Identification Showup Regulations bill was cosponsored by Bacon and Democratic state Sen. Julie Gonzales. The goal was to eliminate the subjectivity and suggestiveness in the practice.

“That’s what the bill really does,” said Bacon. “It creates formal practice around the type of identification that all law enforcement has to abide by.”

HB21-1142 was introduced last March, after the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department and the ensuing racial justice protests. The political climate did make legislators more open to the bill, said Bacon, but the perseverance of the Battle family and Together Colorado really pushed it forward.

“They got bipartisan support and it was because they were able to talk to the truth of the matter. I truly believe that justice really does mean something to a lot of people, regardless of their political party,” she said. “Together Colorado was able to remind folks of that.”

Together Colorado met with over 80 legislators. They worked with a lobbyist to draft the bill based on the policies and trainings the Attorney General’s office created. They also talked to progressive district attorneys, public defenders, lawyers, experts, law enforcement and those who’d been wrongly arrested through a showup.

Amelia Power, a criminal defense attorney and former public defender, also worked with Together Colorado. Most public defenders have represented someone who was identified through a showup, she said, but sometimes that suspect will also be included in another lineup with more people. This did not happen with Charles Battle, which made his case the ideal spark to pursue legislation.

“Charles' case is so unique because it's so clear, right? The showup identification was the thing that triggered his involvement in the criminal justice system,” she said. “A lot of times with showup IDs, it's one of the pieces of evidence that the police have. So, his case was just the perfect case to run for this particular bill.”

Power and many others testified on behalf of the bill, including Denver District Attorney Beth McCann, whose office charged Charles Battle with attempted aggravated robbery.

“We definitely need the safeguards in place that this bill will encourage or require. Denver's already implemented these safeguards,” she said during her testimony. “I believe that this will be really helpful throughout the rest of the state.”

McCann was already familiar with Together Colorado before she began meeting with them in 2019. She attends Montview Boulevard Presbyterian Church, where the organization holds meetings, including the one where Sharon Battle first told members about Charles Battle’s arrest. McCann hopes the new law will increase safety as police become more careful with how they conduct showups and lead the community to trust the police more.

“That's something that we are all struggling with right now, I think, is how to keep the community safe, both from criminal activity, but also from what some perceive to be police misconduct,” she said.

Charles Battle also testified in front of both the House and Senate Judiciary committees. He spoke in support of HB21-1142, asking legislators to “make my pain and my story a positive tool for change.”

His mom, Sharon Battle, also spoke. She brought up that his experience wasn’t an isolated incident and people are misidentified through showups in cities across Colorado and the country.

“I'm counting on all of you to support HB21-1142 that limits the admissibility of show of eyewitness identifications in court and standardizes the use of best practices by law enforcement across the state,” she said.

Both the House and Senate passed the bill and Gov. Jared Polis signed it into law in June of 2021. Bacon was “really proud” of her neighbors for getting the bill passed. She hopes Together Colorado’s accomplishment will inspire more people to get involved in the legislative process.

“I know as a legislator I can't do it without my neighbors. We definitely need base to show up and to say these are experiences and this is what we want to change,” she said. “This is an example of how it can work, and it does work.”

The law went into effect on Jan. 1 and regulates how and when a showup identification can be used. For example, showups must be conducted in a well-lit area and the subject can’t be handcuffed. The courts can also suppress or throw out the showup if it was improperly conducted.

Next year, law enforcement agencies will be required to collect data including the date, technique used, alleged crime, race and gender of the suspect and the outcome of the showup.

Confidence level is another new requirement. If an eyewitness makes a positive identification, the police officer must ask if they are confident, somewhat confident or not confident about their decision.

This is important because eyewitness confidence increases over time, said Anne-Marie Moyes, director of the Korey Wise Innocence Project at the University of Colorado Law School. She added that studies have shown that if an eyewitness has low confidence but gets positive feedback from an officer, their confidence goes up.

“What you want to do is record confidence, like at the very moment that the ID is made, before there could be any kind of feedback like that,” she said.

The new law is a step in the right direction, said Moyes. But once a suspect identified through a showup gets to court, there aren’t many consequences if the regulations aren’t followed.

“What it means is that the court has to take into account in its own evaluation of the constitutionality of the ID, that the police did not follow procedures and that they therefore might have engaged in what is a suggestive process," she said. "But it doesn't mean that the ID is suppressed and cannot be admitted at trial.”

Happy but uncertain about the new law

Charles Battle is 21 years old now and is conflicted on the new law.

“I feel great, actually,” he said. “But I'm doubtful on the difference it's gonna make really. I think a lot of our justice system needs to be just straight upgraded and replaced.

It’s been three and a half years since he was misidentified through a showup and he’s still working through the trauma.

“It's an afterthought in my mind. It's definitely there,” he said. “I just try to take things day by day.”

Sharon Battle says the ordeal has been hard on the entire family and she too has mixed feelings.

“I think it was phenomenal in terms of the work we were able to do. But at the same time, I feel like it's only the beginning of some sort of accountability,” she said.

She now sees herself as an activist and organizer and wants to start a "Black mamas group" to keep holding those in power accountable.

“If we're present and our voices heard, I believe that we can make a difference that's relevant to our community,” she said.

Charles Battle is also looking towards the future. He's working fulltime but hopes to get back on his original path soon: going to college and starting his own business.

“I'm just getting back on track,” he said. “Just, you know, fixing my life up.”