Can public art make people feel happier and more connected? Research from an experimental collaboration last summer in Denver says it can.

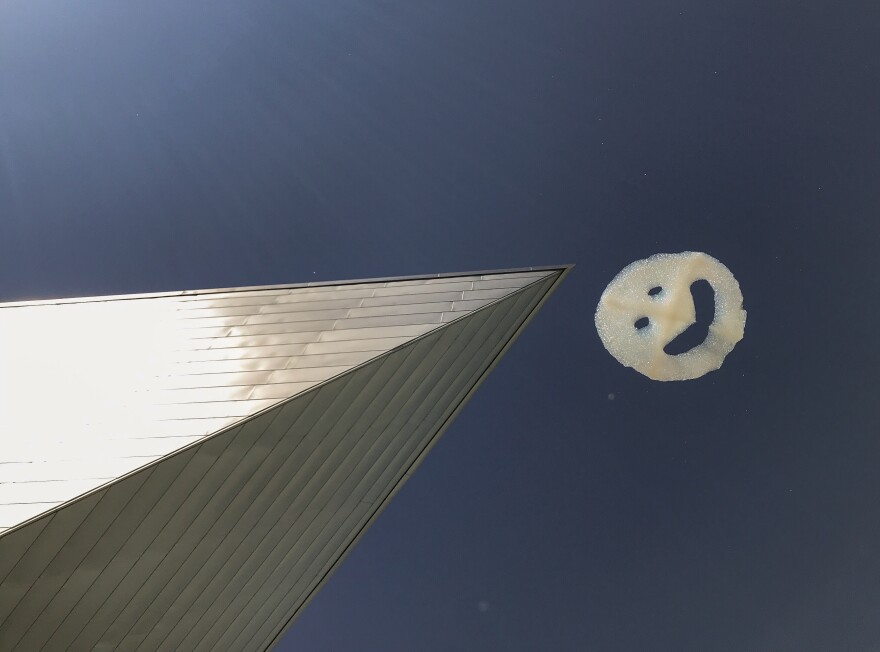

British artist Stuart Semple’s six-week, art intervention called “Happy City: Art for the People” focused on using public art to break down social barriers and nurture well-being with exhibits such as happy-face bubble clouds and an inflatable dance floor in the middle of downtown.

Meanwhile, a research team led by urbanist Charles Montgomery studied several of the installations to gauge the project’s success. The group surveyed participants from two projects: Multi-modal Altruism and Emotional Baggage Drop.

In the baggage drop piece, commuters at Union Station were able to anonymously share their feelings with strangers. The goal: to encourage feelings of empathy and social connection.

“In the iPhone age everybody’s staring at their phone,” said Mitchell Reardon, a senior lead researcher with Montgomery’s consulting organization Happy City. “You don’t think that any stranger wants to connect with you in a public space and when given the chance and having this novel way of doing so, people were very much drawn to this.”

Semple was inspired to do the project, which was sponsored by the Denver Theatre District, in-part by Montgomery’s book, “Happy City.” The book, as well as Montgomery’s consultancy group, focus on how urban planning can be used to improve a community’s health and well-being.

Semple was interested in understanding whether public art could help to create social connection, diminish anxiety and build social trust, Reardon said.

In analyzing the results of the survey:

• Emotional Baggage Drop participants were less likely to report feeling that they had friends or family to rely on for emotional support. This was particularly evident among male participants

• People who participated in Emotional Baggage Drop were more likely to report being optimistic about the future than non-participants.

• Among Denver residents, non-participants were found to be more trusting in other Denver residents than participants.

“People were using Emotional Baggage Drop as a social service that was otherwise lacking, and it was providing real public good,” Reardon said. “(Also) people left feeling more open and willing to express greater vulnerability.”

The Multi-modal Altruism project studied whether the transportation choices people make have an impact on their generosity.

Researchers completed a short survey with a variety of commuters -- car, bike, bus, light rail and pedestrians -- during morning rush hour, Reardon said. They were then told that they would receive $10 for their participation.

“That made people pretty happy,” Reardon said. “But that was just setting the stage for what we were really trying to find out.”

At the end of the survey, participants were told that as part of the project, the researchers were collecting donations for the Mental Health Center of Denver and that, with no obligation, they could choose to donate some or all of the $10.

People who rode bikes were the most generous -- donating an average of $7.36 -- followed closely by pedestrians and drivers. Participants who took the bus and light rail were the least generous -- donating an average of $5.75.

“We were a little bit surprised by the findings,” Reardon said.

While they expected that people who were active in their commute would be generous, thanks in part to the endorphins released by their physical activity, he said they didn’t think drivers who were dealing with rush-hour traffic would have a similar response.

After controlling for income, researchers found that having control over their journey seemed to have the most impact on generosity, Reardon said.

“When you’re taking the bus or train, there’s a certain degree of uncertainty,” he said. “You’re waiting, and the wait times may not be accurate, and there may be delays. You’ve had to give up a certain amount of control and comfort to take this (mode of transportation).”

The findings suggest that more accurate schedules could improve altruism, Reardon said. Additionally, modes such as shared bikes and e-scooters could make getting to the bus or train more enjoyable.

“We think that urban planners, designers and decision makers in Denver and elsewhere would do well to look at these findings and see if there are ways that they could implement them to a certain degree, at least in the public realm,” Reardon said.