Caprice Lawless peruses the aisles at the Sister Carmen Community Center and food bank near her home in Louisville. As she draws closer to the produce section, she sees a heap of squash which a volunteer says will not count against her bi-monthly allowance. She heaves one into her shopping cart, just as another volunteer plops down bins of fresh, tiny Brussels sprouts.

“Holy moly!” she exclaims with delight, before bagging up several of them. ”Look at these little tiny Brussels sprouts.”

Lawless is 64. She’s been teaching English and composition at Front Range Community College in Westminster since 1999. She’s an adjunct professor -- meaning she works part-time and receives no benefits.

At home, Lawless unpacks her groceries and puts them away. Her house is cozy and well-kept. You’d never guess she has three roommates.

“In order to survive on an adjunct’s wage, I have to rent out most of my house. Seventy-five percent of my house. I have three housemates,” she says. “I get most of my food from the food bank, and I also work with Boulder County Human Services, so I have [a] very heavily subsidized by the taxpayers health care plan”

Founded in 1967 by state lawmakers, the Colorado Community College System oversees 13 colleges, including Front Range Community College where Lawless teaches.

Lawless is part of a group of CCCS adjuncts who have been fighting for a pay raise for years. As state employees, many of their appeals happen at the state legislature -- and routinely, they fail.

The ongoing conflict between CCCS leadership, legislators and instructors is emblematic of a much larger national crisis in higher education: As higher education institutions cut costs by relying more on a part-time workforce, how can those who studied for years to join the teaching profession keep a roof over their heads?

Realities of being adjunct faculty

“I took a woman to the food bank once - she was a PhD - and she cried,” Lawless says. “She said, ‘I can’t believe I worked that hard to get my PhD and now I have to grovel like this for food for myself and my son.’ It was really heartbreaking.”

She says it’s not easy for those who dreamed of teaching at the college level to swallow the changing realities of the profession. Full-time work, benefits and job protections are harder to attain than ever. Almost all colleges rely on contingent or adjunct faculty. These instructors are part-time professors with no benefits like health insurance or paid time off.

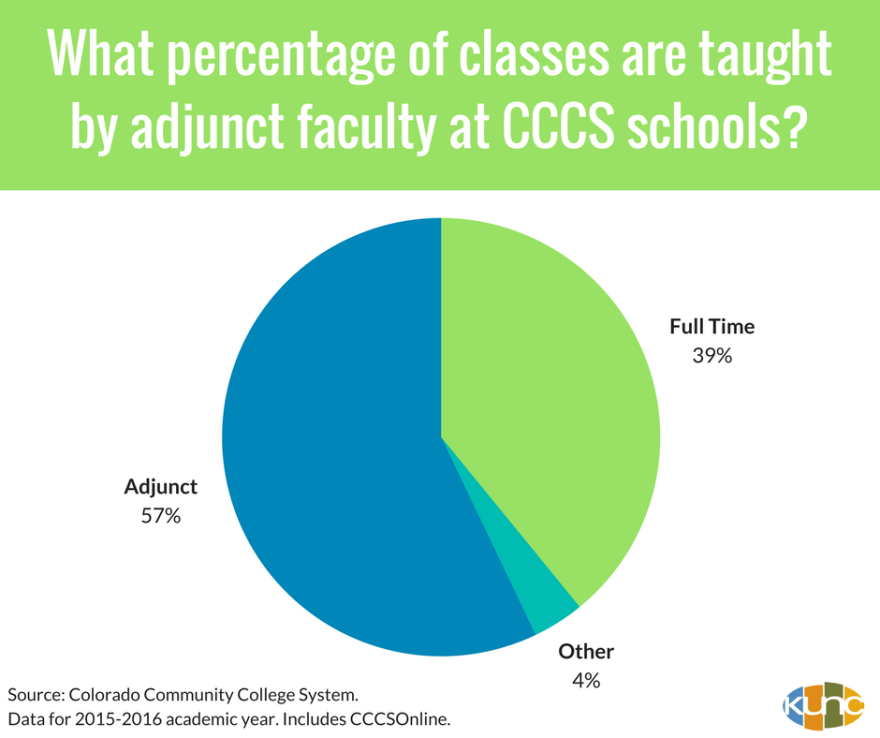

Over the last several decades, it’s these professors who end up teaching an ever-growing share of courses at most colleges across the country. At community colleges, those numbers typically trend higher. A 2014 report from the Center For Community College Student Engagement found that adjuncts teach almost 60 percent of all community college classes in the U.S.

“Community colleges or two-year public institutions, they rely on part-time faculty more heavily than four-year institutions,” says Florence Ran, a senior research assistant at the Community College Research Center at Columbia University in New York.

According to Ran, as much as 80 percent of the faculty at some community colleges are part-time or adjunct professors. Not only does this impact an instructor’s bottom line, but it can also negatively impact students.

"I took a woman to the food bank once - she was a PhD - and she cried."

“They have less incentive to engage with their students,” says Ran, “and there [is] research showing if a student gets a part-time faculty in their first term of college enrollment, they are less likely to persist in the second year of study.”

Statistics from CCCS appear to align with this national trend. Forty-eight percent of students enrolling in the fall of 2014 returned to class in 2015. During that school year, adjunct faculty taught nearly 60 percent of CCCS classes, according to data provided by the college system.

The Center For Community College Student Engagement similarly concluded that “too often, students’ educational experiences are contingent on the employment status of the faculty members they happen to encounter. “

This isn’t lost on Lawless - who is something of a self-appointed crusader for the adjunct cause. She serves in the Colorado chapter of the American Association of University Professors. The national group advocates on behalf of professors - even functioning as a sort of labor union in some states - and has devoted significant attention to adjunct issues in Colorado, thanks to Lawless.

Over the last few years, she’s blogged religiously about the adjunct plight on the Front Range Community College AAUP website, written and distributed a cookbook for adjuncts trying to stretch a dollar and even coordinated carpools to local food banks. She’s also encouraged her colleagues at some CCCS schools to start smaller chapters of their own. To her, there’s strength in numbers. On average, adjuncts within the CCCS system are paid between $2,200 and $2,500 per course -- before taxes. After doing her taxes for 2016, Lawless says she made a little bit more than $16,000 for teaching seven classes total.

Adjuncts aren’t the only ones asked to do more with less

“Obviously I would love to be able to pay more to our adjunct instructors, but unfortunately we are not funded at a level from the state that would allow us to do so,” says Nancy McCallin, the president of CCCS.

"Community colleges from the state are funded dead last."

The system is overseen by the State Board for Community Colleges and Occupational Education. In 2015, the board approved a proposal requiring each college to grant annual raises to adjuncts that mirror the annual raises given to full-time professors -- amounting to a roughly 3 percent increase each year. They rejected another proposal for a larger 28 percent raise. Both proposals came from a group of adjuncts scattered throughout the system. Russell Meyer, chair of the board, declined an interview, but says in a written statement that the larger pay hike was “not realistic - or even possible.”

He went on to say that it was “important to note that we increased adjunct pay at a time when our state financial support declined and when state classified employees received no pay increase.”

McCallin echoes Meyer’s sentiments.

“We are told by the General Assembly to keep our tuition low and affordable in order to provide higher education opportunities to Colorado residents. We are also told to operate on the lowest amount of state funding per student amongst all of the institutions of higher ed in the state of Colorado,” she says. “Community colleges from the state are funded dead last.”

In January, McCallin -- along with other community and technical college leaders -- testified in front of the Joint Budget Committee to request more funding for the college system. However, she says the college has other needs that take precedence over adjunct wages.

But pay is only one criticism facing CCCS.

Changing careers at 62

“I used to teach four classes several years ago, and they had me down to two,” says Larry Eson, a former CCCS professor.

Eson has a Ph.D. -- a rarity among community college professors -- and taught English at two community colleges for 15 years. All the while, he held out for a full time teaching position. He was considered for one, but was ultimately passed over. That, along with dearth of steady work and lack of benefits finally led the 62 year old to quit and search for a new career.

“They’d been cutting back classes,” he says. “ So I was making even less money than I had made before”

After getting priced out of his basement apartment, he has settled into a new apartment, and is juggling several odd jobs as he pursues his new career as a grant writer -- in an unpaid internship. “I would say I’ve pretty much given up on teaching for CCCS,” he says. “If a good teaching position elsewhere comes along, I would give it some consideration. But it’s not my main focus.”

How big is the problem?

Other adjuncts interviewed for this story brought up concerns about job stability -- specifically, the ease with which they say adjuncts are let go and the lack of due process rights that would allow them to appeal terminations. Most say they have no offices, and are not paid to work with students outside of the classroom.

McCallin says the complaints of a small group of adjuncts don’t adequately represent all of the teachers within CCCS.

“We are doing surveys to try and see how we can improve their satisfaction, but the last survey we did, which was last spring,showed that 75 percent of our adjunct instructors were satisfied or very satisfied,” she says.

But Stephen Mumme, a political science professor at Colorado State University and the president of the Colorado chapter of AAUP, doesn’t buy it.

“That survey that they did, we think, was pretty much a kind of boilerplate kind of feel-good survey. I don’t think it was conducted in a way that could faithfully reflect the attitudes of the diverse numbers of adjuncts in the CCCS system,” he says.

AAUP of Colorado sent a letter -- penned and heavily annotated by Caprice Lawless -- to the state’s legislative auditor last year asking for an independent review to see if CCCS can afford to raise adjunct salaries. They continue to push for legislation offering more job protections.

“We haven’t been very successful, in my opinion, although I think we certainly have got a fair amount of attention in the last three, four years from the community college system,” Mumme says. “They’re aware that there are critics who are advocating on behalf of adjunct faculty.”

The auditor’s office has yet to decide whether or not to take up AAUP’s request. Mumme says they’re working on partnering with a few lawmakers to sponsor bills addressing adjunct issues during this year’s session.

State Sen. Nancy Todd (D-Aurora), who sits on the Senate education committee, hasn’t laid eyes on a bill from AAUP yet this year. She says that in the past, much of AAUP’s legislation has failed because it would have cost too much.

“I remember that there was one bill that had a huge fiscal note, because along with not only the same equal pay was the same equal benefits, and the [Public Employees Retirement Association] cost in and of itself was astronomical,” she says.

Colorado currently faces an estimated $500 million dollar budget shortfall. In years past, cuts have been made to higher education funding to balance the rest of the budget.

Todd says that when it comes to asking for a pay raise, adjuncts should get in line.

“To be very honest, the pay that we give to our teachers, be it at the community college level, K-12, nurses, any and all the above, state employees -- is not ample,” she says. “And so we’re seeing, due to high cost of living and low availability of affordable housing, we’re seeing a lot of people that are really struggling with that. So it is not unique to just one group of people.”

Regardless of where higher education funding falls at the end of this year’s legislative session, the Colorado Community College System does not plan to give adjuncts a raise any time soon, despite the fact that the system continues to grow.

CCCS announced in January that Arapahoe Community College would be getting a new $40 million campus in Castle Rock. It’s expected to be completed in August 2019.