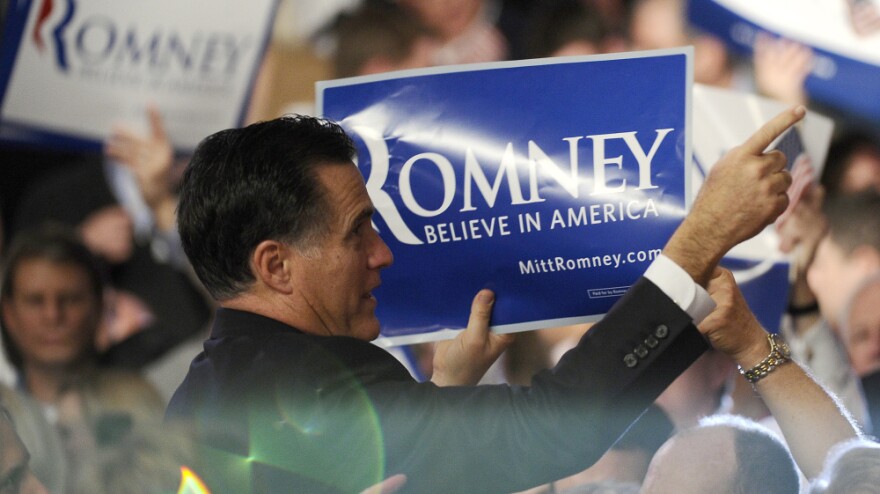

Mitt Romney came away from the New Hampshire Republican presidential primary Tuesday night with a comfortable win, and an uncomfortable reality.

His chief detractor, GOP rival Newt Gingrich, who in recent days has launched a savage campaign to undermine Romney's successful-businessman-makes-best-president narrative, is just getting warmed up.

In South Carolina, where the next primary is scheduled for Jan. 21, a superPAC supporting Gingrich — flush with $5 million from casino magnate Sheldon Adelson — will begin airing a film that depicts Romney as "more ruthless than Wall Street" during his years as head of a lucrative private equity business that bought, sold and closed businesses.

The aggressive attacks, not unusual for the early weeks of primary season, have delighted Democrats, shaken the former Massachusetts governor's operation, and continue to alarm a swath of conservatives anxious for their party to coalesce around the man they see as their best shot against President Obama.

Whether the harsh criticism will make Romney — who last week eked out an eight-vote win in the Iowa caucuses — a better candidate in the long run, as some suggest, or permanently handicap him if he is the nominee, as Democrats hope, remains an open question.

As does how long Gingrich, the former House speaker who finished fourth in Iowa and was in position to finish no better than fourth in New Hampshire, can sustain his onslaught.

Attacks Rattle Party

The attacks on Bain Capital's activities under Romney's leadership have been so pointed, and taken on such a life beyond Gingrich, that the private equity industry's lobbying group put out a press release defending its business practices.

Influential conservative groups and publications have scolded Gingrich and other candidates for the sin of acting like Democrats when they criticize Romney's stewardship of a firm that made money even when it closed businesses. (A Wall Street Journal analysis of 77 businesses Bain Capital invested in with Romney at the helm from 1984 to 1999 found that 22 percent eventually filed for bankruptcy, or closed within eight years after Bain first invested in them, "sometimes with substantial job losses.")

"We'd hope that supporters of the free market would recognize what Gingrich's attacks are: craven political assaults on capitalism and economic freedom," Barney Kellar of the conservative, free-market Club for Growth, told NPR on Tuesday. "Ultimately Republicans and then the American people will render their judgment through the ballot box."

But with Gingrich continuing to amp up his criticism about Romney's tenure as head of the private-equity firm, other conservative heavyweights weighed in.

The editors at the National Review accused Gingrich — and fellow Republican candidates Jon Huntsman and Rick Perry — of engaging in a "perverse contest to be the Republican presidential candidate to say the most asinine thing about Mitt Romney's tenure at Bain Capital."

And the Karl Rove-affiliated superPAC American Crossroads issued a statement strongly supportive of Romney, noting that Gingrich's attacks have resulted in a "major downward impact" on his own support. (A quick follow-up email from spokesman Jonathan Collegio, however, asserted Crossroads "is, and remains neutral" in the GOP primary.)

Investment Class

Interested to hear what those in the investment field have been making of Gingrich's fusillade, NPR turned to David Kotok, co-founder and chief investment officer of Cumberland Advisors, a Florida-based investment advisory firm.

"Romney's business prowess has been turned on him in a very nasty way, but that's the nature of our political system," Kotok says. "The attack on Romney is by a desperate candidate."

It's not that Kotok doesn't believe there's a debate to be had going forward about the special tax circumstances under which Romney and Bain Capital made its millions.

"Romney was involved in an activity that gets a 15 percent carried interest tax break," Kotok says, explaining that the special tax treatment allowed a 15 percent tax rate on certain transactions that Bain was involved in.

"While you were out there working and paying higher taxes, Mr. Workingman, Mr. Schoolteacher," Kotok says, "his enterprise was getting a tax break. Do you think that's right?"

That's a topic worthy of debate, he says, because it involves tax policy, and not how many jobs somebody may or may not have created years ago. Romney's claim that he helped create 100,000 jobs during his tenure at Bain has been the subject of much debate and scrutiny.

"Can Romney describe himself as a job creator?" Kotok said. "I don't know. But he has business capital investment experience. He's been governor. And his personal life seems to be very clear, in order and above reproach. No question about any of that."

But Whom To Trust?

Democrats like Chris Lehane, a veteran of the Clinton White House, however, say that questions about Romney's job creation claims while he was a corporate buyout specialist are indeed legitimate.

It's all about trust, Lehane says, repeating a theme that Democrats are increasingly attaching to Romney.

"In presidential campaigns, candidates get positive and negative storylines," says Lehane, now a California-based strategist. "If the race is competitive, the storylines play themselves out as it relates to who wins the public trust argument."

"Specifically," he says, "who do you trust to make the right economic decisions that will impact you, your family and the country?"

He sees a cautionary tale in what happened to Meg Whitman, the former eBay CEO who was the Republicans' unsuccessful candidate for governor in California in 2010. Whitman, now head of Hewlett-Packard, ran on her economic and job-creating credentials but was sunk when her critics (including Lehane) hit her for firing workers while she took bonuses, for sending jobs offshore, and for mistreating a longtime maid.

"She lost the public trust issue, and her candidacy collapsed," he said.

Democratic commentator Karen Finney notes that Obama became a stronger candidate in 2008 because of his intense battle with then-Sen. Hillary Clinton for the nomination.

Romney has that chance, she says, but so far has continued to stumble.

He was dinged after he told a campaign audience that he, too, had worried in the past about getting a pink slip. (Perry later joked that Romney's worry was whether he'd have enough pink slips to pass out.) And he gave Democrats fits of delight when, in explaining his opposition to the health care overhaul, he said, "I like being able to fire people who provide services to me."

Romney heads to South Carolina Wednesday, where the ground is much less friendly, and where Gingrich and the rest of the field are waiting. It's expected to be Perry's last stand, and maybe the end for another candidate or two.

That's dangerous. Especially for a front-runner who now has to figure out, and quickly, how to resell what had been his strongest selling point.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))