The U.S. Department of Agriculture expects farmers to harvest about 13.6 billion bushels of corn [.pdf] this season, the third-largest harvest in U.S. history. A fraction of that gigantic crop will sweeten our food and drinks, about a third will be made into ethanol fuel and, and when you figure in exports and byproducts, more than half will go to fattening the livestock that become our chicken filets, pork chops, and burgers.

While we don't actually eat field corn - the kind of corn mostly grown in the U.S. - the Corn Belt is the backbone of the meat industry.

"A lot of that corn, since it's going into livestock feed, ends up in us," said Chad Hart, an agricultural economist at Iowa State University.

The average American will consume about 200 pounds of beef, pork and poultry in 2015, according to USDA projections. While U.S. demand for meat has declined over the past decade, it's rapidly growing around the world, with China biting at the heels of U.S. per capita consumption, and other regions, like North Africa and the Middle East, wanting more animal protein in their diets, as well.

This appetite for meat, which began growing exponentially in the U.S. after World War II, is one of the reasons farmers in the Midwest grow so much corn, and so little else.

Farmers planted close to 90 million acres of corn in 2015. That's a similar amount, if not a little less, than the acreage planted when the USDA began tracking corn production in the 1860s. But those 90 million acres used to be spread across farms all over the country.

"Today, we're much more concentrated in the upper Midwest as far as that corn production is concerned," Hart said.

States in the USDA's official Corn Belt, which includes Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Ohio, grow half of the country's entire corn crop. When you add in other Midwestern states, it jumps to close to 90 percent. When the USDA first identified the Corn Belt as a distinct agricultural region, it was small, diversified farming that defined it, not the crop.

"Corn was the dominant crop within their Corn Belt region," Chris Laingen and Cameron Craig write in their article, Adding Another Notch to America's Corn Belt [.pdf], "but the process of rotating corn with oats, wheat, soybeans, and hay and pasture crops, along with feeding most of the grain to livestock, was what held that region together."

Roger Kelso grew up on a farm in western Illinois in the 1930s and '40s and remembers how people farmed back then.

"Everybody around here fed cattle and hogs," he said. "My dad had 200 head of cattle every year and he had 600 head of hogs a year. And the neighbors across the road probably fed out 400 head of cattle."

Kelso said farmers typically didn't put their cows and pigs out to pasture. Instead, they lived on small patches of dirt called "dry lots" and were fed corn, hay and oats that the farmers grew. They also raised chickens and had a team of horses to pull wagons and the plow.

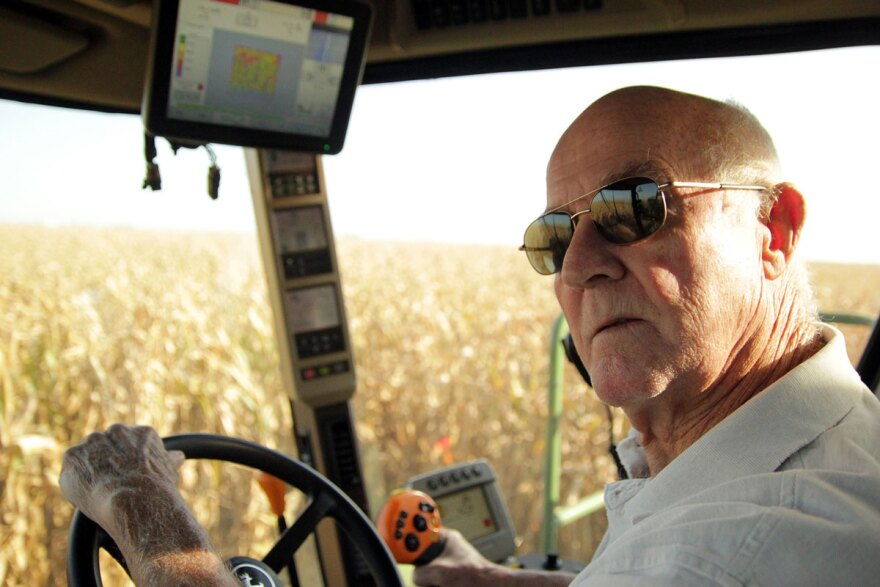

"It's a whole different ballgame now," said Kelso, who still helps his sons, Clarke and Kurt, farm 4,000 acres of corn and soybeans on some of the same land he helped his grandfather and dad farm as a child.

In the 1950s, the diversified operations that defined the Corn Belt began breaking into specialized chunks. Chickens migrated southeast. Cattle were herded southwest. Other types of animal feed, like oats and hay, moved north and west. Corn stayed put in the heartland, where the soil and climate conditions are most suitable for the grain.

The Corn Belt's animal sector, which accounted for three-quarters of the value of the region's agricultural production in 1930, dropped to a third of the value of production by 2013, according to the USDA's Economic Research Service. Chad Hart, the ISU economist, said farmers opted to grow either animals or their feed in service to efficiency.

"We figured out the assembly line, if you will, definitely has some advantages," Hart said. "[Farmers] could lower their cost structure; they could improve their production patterns, when they concentrated on fewer enterprises."

Maureen Ogle, historian and author of the book In Meat We Trust, said this move away from diversified farming and toward specialized production in the middle of the 20th century was supported by the federal government.

"In the wake of the Great Depression and World War II, the federal government made a concerted effort to get small, inefficient farmers off the land," she said. "They supported farmers who were willing to treat farming as a business."

Additionally, she said, the federal government began subsidizing corn production.

"Many farmers who raised livestock said, 'The heck with it. If the government's willing to pay me to raise corn, that's what I'm going to do,'" Ogle said. "At least, then, I could take a day off once in a while.'"

Instead of feeding animals on the farm where the grain is grown, corn now travels several hundred miles, sometimes more than a thousand, to the livestock that consume it. That journey often begins at places like Western Grain Marketing in western Illinois.

At WGM, a long train track wraps around cement and silver steel grain bins that rise 60 feet out of the near-endless sea of golden corn. A few times a month, a 110-car train jumps onto the track and lurches forward, positioning each car underneath a spout that unleashes a waterfall of corn. Once loaded, the train chugs down to cattle feedlots and ethanol plants in Texas and Mexico.

"We're bringing stuff in, shipping it out constantly," said Scott Sims, a business manager at WGM.

Even when the corn is destined to become fuel, Simms said, some of it still ends up on feedlots in the form of an ethanol byproduct called Dried Distillers Grains. Recently, the trains have also been hauling corn to Pilgrim's Pride chicken houses in Texas.

"They go through one shuttle - 450,000 bushel - in six days," Sims said. "That's a lot of corn for chickens."

How many chickens?

"I have no idea," Sims shrugged. "We tried to figure that out one time and we got into the millions and finally gave up. It's a lot."

Unlike chickens and cattle, a lot of hogs stayed in the Midwest, though many still moved off grain farms and onto operations that specialize in producing pork.

It's common for hog farmers to raise tens of thousands at a time, inside uniform, climate controlled, concrete barns. Shielded from the elements, and well fed on corn and soybeans, 15-pound piglets plump up to 300-pound hogs in as few as six months.

Pork production has gotten so efficient that a few years ago, some grain farmers like the Kelso's were able to bring hogs back.

Adding in hogs to the operation possess little financial risk to the Kelso family, who don't actually own the animals. They just fatten them up for the hog company, TriOak Foods. In exchange, the Kelsos get paid a fee and keep the hog manure to spread on their fields. That helps them grow more grain, to feed to more livestock to, ultimately, produce more meat.