It was his father, Morry, who got Glen Weseloh into the neon business.

“My dad had been bending since the end of WWII,” Weseloh said. “When he got to be 65, the union came to him and said, ‘You can no longer work and receive all your benefits.’”

But Weseloh wasn’t about to let his dad give up doing what he loved. So in 1985 the duo went into business together, and Morry’s Neon Signs was born.

“My weekends (as a kid), when he would work I would go in with him and watch and learn and so it kind of got into my blood,” he said. “I didn’t think I would continue it after he was gone, but it’s a fun business.”

In the last 30 years, Weseloh and his dad created several of Denver’s iconic neon, including signs for Union Station and the former Wonder Bread bakery. In that time, he’s seen lots of changes in colors and styles. But as for the manufacturing behind neon itself? Very little has changed.

“Neon is funny in that, in essence, the way that it’s manufactured -- it’s done exactly the same way that it started in 1923,” he said.

Glass tubes are shaped and then coated with minerals called phosphors. The phosphors are illuminated via electrodes placed at each end of the tube, running an electrical current back and forth 50 times a second. That ignites the gases -- neon and argon -- producing the colored light.

“We can come up with close to 80 different colors just with the difference in phosphors and the gas that we use,” Weseloh said.

Over the decades, neon has gone from the ultramodern, “Googie”-style of the 1950s and ‘60s, to the less flashy, pan channel lettering that was popular in the strip malls of the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Things changed again around 2010.

“All those pan channel letters in the shopping centers went to LED,” Weseloh said.

Neon began to fall out of fashion. Businesses were coming and going too fast to make investing in a big, neon sign seem worthwhile. If they already had one, they weren’t willing to spend the money to maintain or restore it. Instead, they’d let it go dark, or to the landfill.

For Denver resident Corky Scholl, that was unacceptable.

The Colorado photojournalist first fell in love with neon while working the overnight shift at a TV station in Minneapolis.

“Sometimes I would have time to go out and just get beauty shots,” Scholl said. “And I found the best, nighttime beauty shots were usually the ones that were lit with neon lights. Just because the quality of light was so much richer.”

When he moved to Denver to work for 9News, Scholl was drawn to the historic neon on Colfax Avenue, but dismayed to see how many were in disrepair.

“You know, I’d just seen one too many of these signs get taken down,” Scholl said. “I just decided that enough is enough. I need to actually do something about this. I didn’t know what I could do, or what I should do. But I knew that somebody had to do something.”

In 2012, he created “Save the Signs.” The Facebook Page is dedicated to promoting and preserving Colorado’s neon heritage. Two years later, Colorado Preservation, Inc. added all the neon signs along Colfax Avenue to its list of Most Endangered Places.

According to Scholl, neon became so ubiquitous in the 1960s and ‘70s that the bright lights eventually lost their shine.

“People just started taking them for granted,” he said. “They were everywhere ... and so, you didn’t think they were special. And that’s unfortunate, because you look at some of the signs that have been lost and it just breaks your heart.”

Some of the signs even became illegal, Scholl said.

In the early 1970s, Denver and other Colorado cities banned neon signs featuring flashing or chasing lights, dubbing them hazardous to motorists. For decades, the sign for Pete’s Kitchen on Colfax showed a chef holding a pan with a pancake. This year, the owner received a variance allowing those pancakes to once again “flip” through the air and land on a plate, the way they were designed to.

Today, more signs are being restored and showcased in all their glory. According to Weseloh, nostalgia is big.

“Now it’s more art and more exposed neon,” he said. “A lot of retro; a lot of restoring projects.”

There are only two neon shops left in Denver -- Morry’s and Acme Neon Signs -- but Weseloh said he sees it as a badge of honor to be one of the last shops standing. There also seems to be plenty of business to go around.

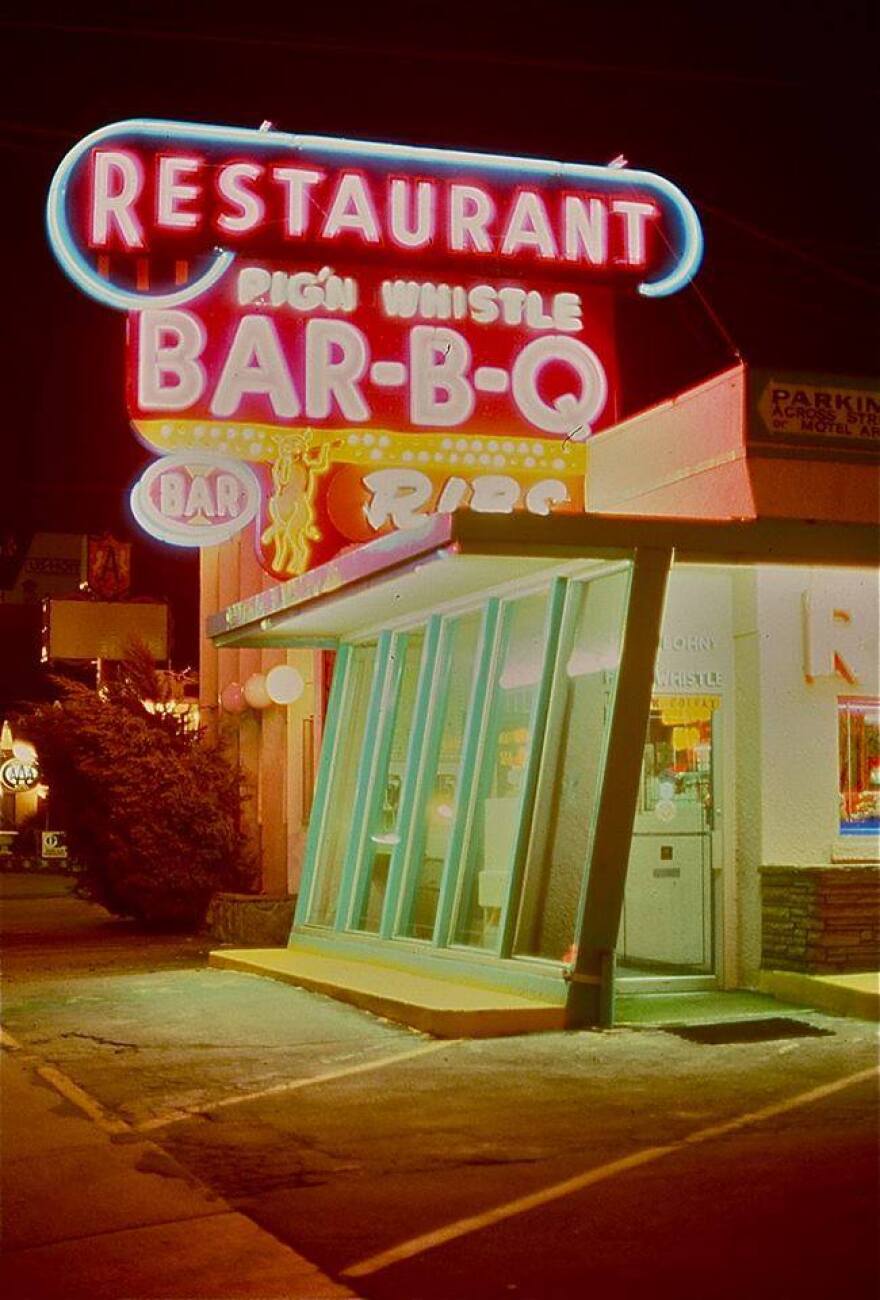

Weseloh said he’s doing almost as many restoration projects as he is new ones. Right now, he’s working on the sign for Eddie Bohn’s Pig ‘n’ Whistle. The Denver diner was owned by the boxing mogul and was a place where politicians, professional athletes and movie stars rubbed elbows. It was even featured in a scene in the 1978 Clint Eastwood film, “Every Which Way but Loose.” The building burned down in 2010, but one of its signs survived. Now, even though the new business is a marijuana dispensary, the owners are still restoring the sign, just as it was.

“That’s very rare that a business owner kind of embraces the history of a place like that,” Scholl said.

That’s why he accumulates discarded neon from restaurants, bars and other businesses. Scholl has been working with the Stanley Marketplace in Aurora to eventually create a museum to showcase the signs once they are restored. But he doesn’t like to think of himself as a collector.

“My goal is to keep them where they’re at, keep them on the street, and just raise awareness and appreciation of these signs,” Scholl said. “So that the owners don’t want to take them down. They realize they have something special.”

To Weseloh, one part of neon’s allure is obvious. He said he has tubes that are more than 70 years old and still burning bright.

“With neon there isn’t an element or anything to burn out,” he said. “If it’s processed right, it should last forever.”

If he and Scholl have anything to say about it, neon’s place in Colorado will last forever, too.