In 1948 a plane crash in Los Gatos, Calif. claimed the lives of 32 passengers, including 28 Mexican farm workers. In many of the news accounts, only the four white crew members were listed. The rest were only “deportees.”

While doing research for a book in 2010 author Tim Hernandez happened upon newspaper clippings about the accident. It set him on a path to find out the names and stories of those 28 passengers. But it also led him to one more story that needed to be told -- one that began in Greeley, Colo.

“I wanted to find the origins of the song,” said Hernandez, who went on to write the book All They Will Call You about the victims and the song from which the book takes its title. “That was part of the research from the beginning, because I knew that the song was vital to this.”

It turned out that soon after the crash, folk singer Woody Guthrie was so struck by the anonymity of the Mexican victims that he penned the poem Deportee (Plane Crash at Los Gatos). It took another 10 years before Guthrie’s words would find a melody thanks to a Colorado State University student named Martin Hoffman.

“Everyone attributes this song to Woody Guthrie,” Hernandez said. “We don’t hear the name Martin Hoffman.”

In the late 1950’s, Martin Hoffman was an English major at CSU. He also was a founder of the university’s Ballad Club.

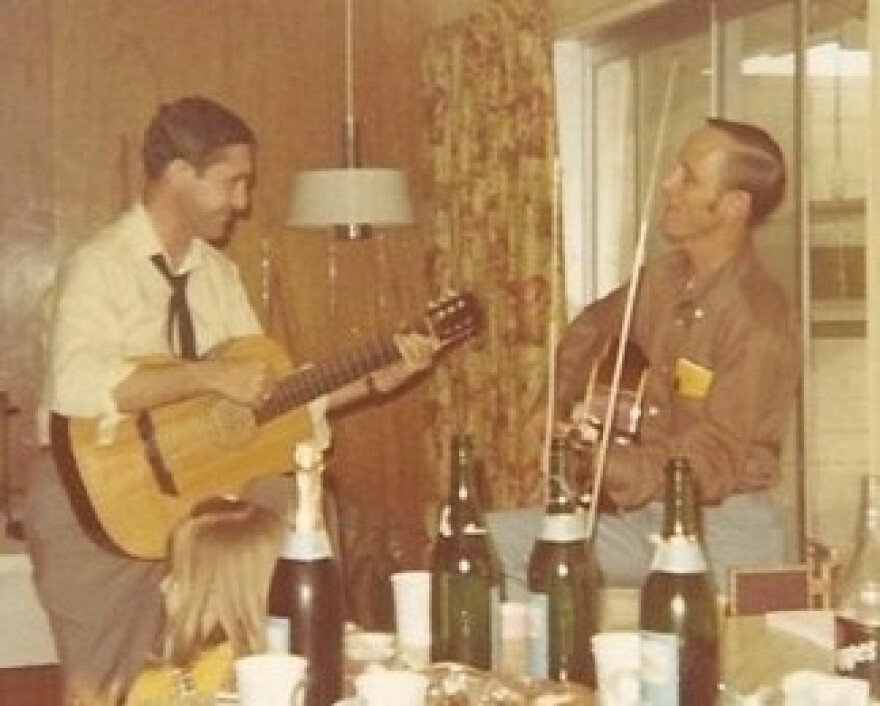

On April 23, 1958, the club hosted a concert with folk singer Pete Seeger on the largest stage in town -- the Lincoln Junior High School auditorium (now Fort Collins performance venue the Lincoln Center). At an after party at Hoffman’s tiny apartment in Greeley, students took turns performing songs for their musical hero.

According to accounts from family members, Hernandez said a sleepy Seeger began nodding off when Hoffman began playing a song he’d just written using Guthrie’s poem as the lyrics.

“As Martin’s playing that song, right here in Greeley for the first time, Pete Seeger takes a notepad out, writes a few things down, puts it in his pocket, says, ‘Thank you guys, good night,’ leaves,” Hernandez said. “Two months later, Martin receives a letter in the mail from Pete’s manager saying Pete is going to record that song and he wants to co-credit (Hoffman) with Woody Guthrie for that song.”

During Hernandez’s research into Hoffman, he found an original recording of Hoffman singing “Deportee” from Diane Vigeant.

Vigeant’s father, Jerry Davich, was one of Hoffman’s closest friends. After Davich died in 2007, Vigeant was going through her father’s old boxes.

“And I found this little pack of four cassette tapes in a sandwich-size Ziploc bag with a table of contents typed on a manual typewriter with my dad’s handwriting on it,” she said. “And on each tape, it said ‘Mart’ and a series of years.”

On the first tape, track number four was listed as “Deportee -- original recording.” Vigeant has since returned the original tapes to Hoffman’s family. They have not authorized the release of any of the tapes. But as Hernandez has heard that original recording.

“What’s interesting is, Martin actually speaks before he records the song,” Hernandez said. “He tells his friend, Dick Barker, ‘This song, Dick, ‘The Plane Wreck at Los Gatos’, it was written by Woody Guthrie.’ And then he goes on to tell us that those words needed a melody to it, and he says, ‘I put the two together and here’s what happened.’”

Since its original release, “Deportee” has been covered by dozens of artists, including Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Bruce Springsteen, Ani DiFranco, Willie Nelson, Concrete Blonde, Billy Bragg and most recently Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello.

But while the song is well known, its origins were largely hidden. After graduation, Hoffman went on to start a demonstration school on the Rough Rock Reservation in Arizona. Later, he committed suicide.

Hoffman’s friend Judy Collins went on to write “Song for Martin” in his memory in 1973.

In a 2012 interview with The Washington Times, Collins noted that Hoffman singing “Deportee” was the first time she heard a Woody Guthrie song, but that even she didn’t know he wrote the lyrics until recently.

Hoffman’s contribution became more of a footnote. Until Tim Hernandez.

While researching for his book, Manana Means Heaven, Hernandez found clippings about the accident in Los Gatos Canyon. Discouraged by the lack of acknowledgement towards the Mexican passengers, the author tracked them down to Holy Cross cemetery in Fresno. They had been buried in a mass grave.

“It moved me,” Hernandez said. “There was a placard there that was very anonymous. It just said, ‘28 Mexican citizens died in a plane crash. January 28. Rest in peace.’ I just felt pulled into the story. I had to find out who they were.”

It was then Hernandez also connected the song “Deportee” to the incident.

“I had heard the song growing up, a few times, probably from Arlo Guthrie, and then later on from Bruce Springsteen -- one of my favorite versions,” he said.

The research became personal. The crash happened in his home county of Fresno and Hernandez’s own family roots included migrant grandparents who worked Colorado farms in Greeley and Fort Lupton.

“Having seen my family struggle, (…) having sort of moments where they were silenced in their own lives made me invested in the story,” Hernandez said. “And so, I began to listen to the song differently.

“I wanted to find the origins of the song,” he said. “That was part of the research from the beginning, because I knew that the song was vital to this.”