This story was produced through a collaboration between the Mountain West News Bureau and Climate Central.

In northern Nevada, east of Reno, a mountainous desert unfolds like a pop-up book. Wild horses on hillsides stand still as toys. Green-grey sagebrush paints the sandy land, which is baking under the summer sun.

On a 10-acre slice of this desert, people are working to turn this sunshine into paychecks. As society phases out fossil fuels and builds huge new solar energy plants, this region is grabbing a share of that green gold rush by retraining workers for work that is spreading across the West.

At this training center for the Reno branch of the Laborers’ International Union of North America, Francisco Valenzuela uses a wrench to secure brackets to a long steel tube on posts about four feet off the ground. What looks like the start of a giant erector set is the support structure common on large-scale solar farms.

“The brackets, they hold the panels and we set it up,” said Valenzuela.

A few years ago, Valenzuela did electrical work for a solar project not far from here – the 60-megawatt Turquoise Solar Farm. Now, he’s gaining more skills so he can land more jobs. The 43-year-old is originally from Sonora, Mexico, but lives in Reno for trade jobs in northern Nevada. He has two kids in Las Vegas and visits when work is slow.

“You stay busy the whole year working,” he said.

It’s good pay, too, he added, with some companies paying $20 to $30 an hour, or more.

These days, clean energy infrastructure construction is booming and with that, so are solar industry jobs. Nevada has jumped to the forefront in retraining workers for jobs at large-scale solar plants, so much so that now, workers from other states are coming here for guidance.

This year, more than half of all new power generation nationwide will be solar. Developers plan to install roughly 29 gigawatts of solar power – more than double the current record. In Nevada, planned projects this year could increase solar power by almost 1,600 megawatts.

Alt description: An interactive map shows operating and planned solar plants across Nevada, primarily in the northern and southern parts of the state. The largest operating plant is Eagle Shadow Mountain Solar Farm in Clark County, which started in 2023 with a capacity of 300 megawatts. The largest planned plant is Chill Sun Solar Project in Nye County, which is planned to start in 2027 with a capacity of 2,250 megawatts.

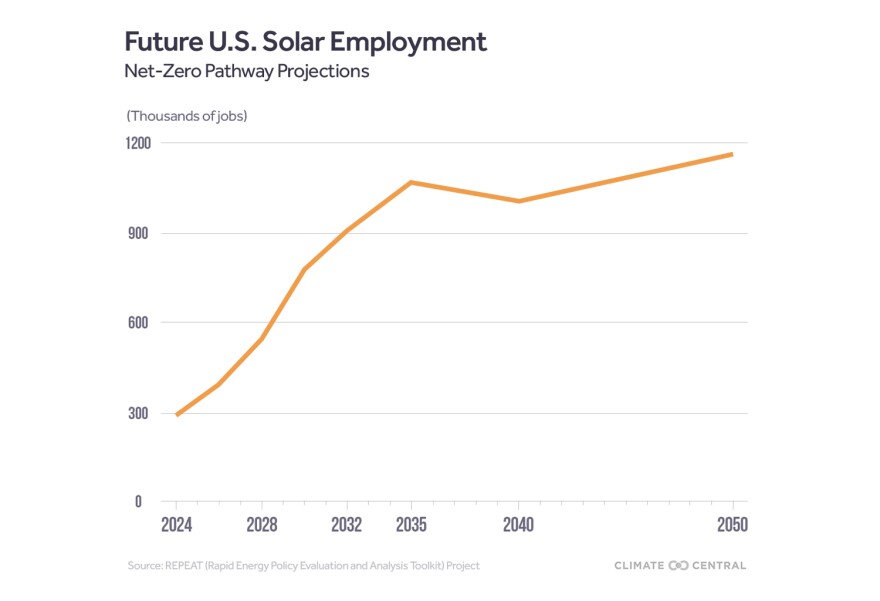

The Solar Energy Industries Association says about 800,000 new workers will be needed in less than a decade. That’s to push the nation’s electricity generation from solar to 30% by 2030. Solar accounted for less than 4% last year.

“Employers have a need, and they’re hiring, and the pace with which we are hiring and growing is fast,” said Cynthia Finley, who leads workforce strategies for the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, or IREC. The organization says there were more than a quarter million solar workers across the country last year.

But nearly half of the industry’s employers said it was “very difficult” to find qualified applicants.

“The biggest challenge, I think, for everyone is finding those connections to where the jobs are,” Finley said, as well as “finding the training to give you those skills and qualifications to do that job.”

Nevada is taking the lead in developing that workforce for its residents. The state has the nation’s largest solar workforce on a per capita basis and ranks eighth in solar jobs, with more than 7,500 people working. That workforce grew 5% last year alone, the energy council says.

Many of those workers are working in the deserts surrounding Las Vegas, says Guy Snow. He trains electricians with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers for solar jobs.

“I think we’re ahead of the game as far as being able to build large utility scale plants,” Snow said. “We have some of the largest plants being built around Vegas.”

That includes the $1.2 billion Gemini project. The 690-megawatt solar plant is being built on roughly 7,000 acres, making it the nation’s biggest. Gemini is expected to be completed by the end of the year and generate enough electricity to power 260,000 homes.

“We have 300 electricians out there right now working on that solar plant,” Snow said. “I’m pretty confident we’re going to be able to handle the entire needs of the state of Nevada, for solar and storage.”

Despite the economic and renewable energy benefits, projects like Gemini also can damage the environment.

“We are very much in support of solar as a key to our renewable energy transition,” said Patrick Donnelly, Great Basin director for the Center for Biological Diversity. “What we do have concerns with is the current push toward developing these projects largely in intact desert habitats and undeveloped landscapes.”

Donnelly says developers should build in locations that humans have already disturbed, like abandoned mines or agricultural lands. But, he adds, the biggest threat to biodiversity is climate change — and the main cause is burning fossil fuels.

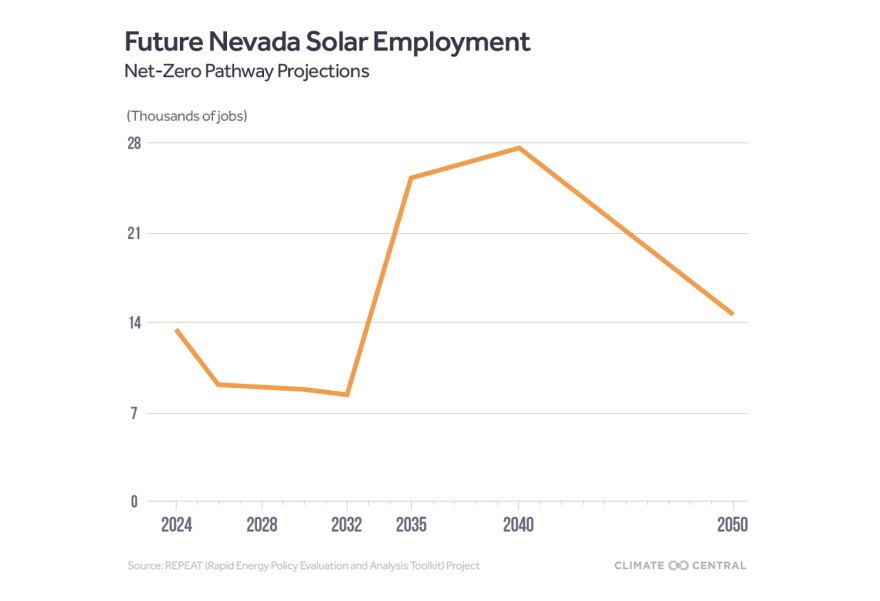

That means more solar farms, and a growing workforce, at least for now.

Although solar jobs soar when installations are underway, at some point, those jobs will run out. Last year, almost 172,000 solar jobs were with project installation and development firms, and only around 16,000 were in operations and maintenance, according to the latest National Solar Jobs Census.

The electrical workers union is addressing that issue by making sure trainees are qualified, not just for big solar projects, but to work as general electricians on the steady stream of construction jobs around Vegas.

But there have been other hiccups in the growth of solar employment. Supply chain concerns and the specter of new tariffs on solar panels temporarily slowed large-scale installations last year. The Solar Jobs Census reported a decline in utility-scale jobs, even as residential installation jobs increased.

Over the longer term, however, the trend is strongly upward. If projects move ahead as planned in Nevada, solar capacity in the state will double by 2029.

Back in northern Nevada, Paige Den-dekker is also getting trained on solar work. The 57-year-old journeywoman is from Montana and used to be a flagger for mining operations. But she’s seeing more and more solar opportunities, especially in Nevada.

“You make better money. It’s better for the environment,” she said. “And it also creates a lot of jobs for our apprentices and everybody that’s in the laborers’ union.”

The Reno branch of the laborers’ union readies an average of 25 people a month for solar assembly and installation. And sometimes a lot more, says Al DeVita, the center’s director.

“Lately, a lot of people have been coming in for the solar training that we’ve been providing – and it’s a big hit,” DeVita said. “We invested a lot of money in this training because we know there’s a lot of work, and our piece of it is to try and provide a skilled workforce.”

And the union is helping provide more skilled instructors nationwide. This year, laborer trainers from across the country have been coming to the Reno desert to learn the tricks of the trade.

“I would say we’re way ahead of the curve,” DeVita said. “Close to 50 instructors from all around the country are coming in here to see what this site is – lots of people taking pictures, there’s a guy out there with a drone – and they’re trying to figure out how to implement it at their site.”

In the meantime, trainers in the Nevada desert will keep preparing workers to power the green gold rush in the West.

Climate Central’s Joseph Giguere contributed data reporting.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, KUNC in Colorado and KANW in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2023 KUNR Public Radio. To see more, visit KUNR Public Radio.