Orion Aon spent a lot of time fishing, hiking and camping growing up in Santa Fe, New Mexico. When he was 10 years old, he went on a mushroom hunt with his friends that only increased his love for nature.

“I remember just being taken with the experience of, like, this treasure hunt for these fascinating and unique organisms,” he said. “I'd spent my younger days just sort of wandering and climbing trees and asking questions and experiencing, and this sort of attachment to (the idea) that ‘I can do that while also finding delicious food.’”

He and his friends continued to do annual foraging expeditions – gathering food in the wild – throughout high school and college. It’s what led Aon to start Forage Colorado in 2015, an educational platform for budding foragers.

During the pandemic, regional interest in foraging in the forests and wild lands that the Mountain West has to offer grew rapidly. It wasn’t long before experts were sharing their opinions on TikTok or writing books about the topic.

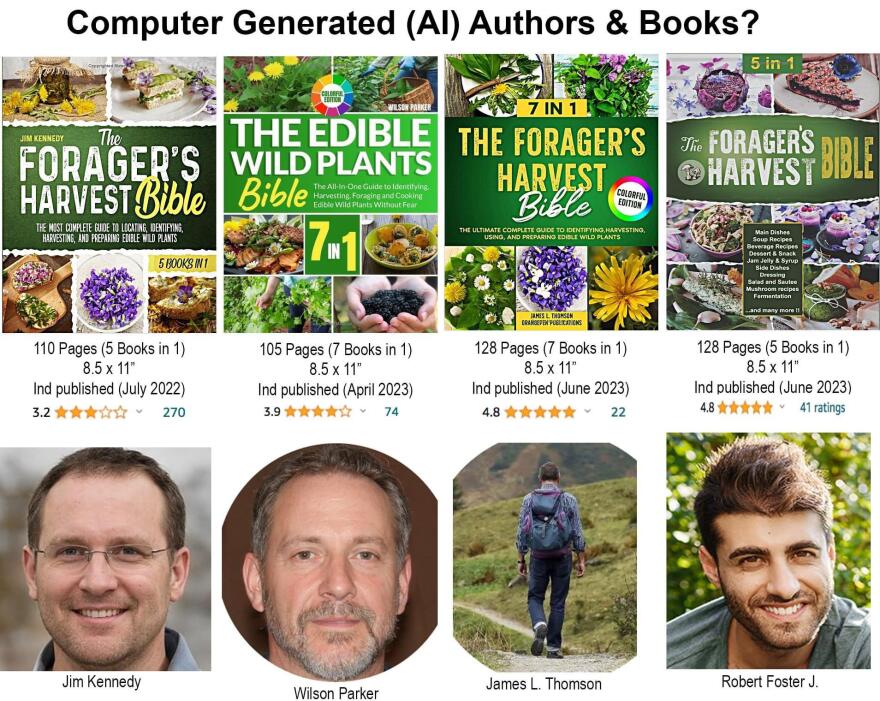

But recently, Aon and some of his foraging peers started to notice something strange about foraging books online. Some of the books would be only around 100 to 200 pages, a lot shorter than the books written by his peers, which tended to be around 500 pages. When they tried to look up the authors, no credentials or factual information came up. And many of the books had the same title.

That’s because some companies have been using AI to write foraging books and sell them quickly for a profit. With a simple guiding prompt of, “Write me a book about how to forage,” a computer could come up with material in only a few seconds. Currently, over 3,000 books on Amazon list ChatGPT as an author, from children’s books to neuroscience texts.

But while AI has its uses, Aon said, in the foraging world, it could lead to dangerous outcomes.

Inside, many of the AI-generated foraging books have oversimplified or inaccurate descriptions about plants and flowers, Aon said. Some of the books contain pictures of toxic species in place of non-toxic ones that look very similar. This is because AI pulls information from sources that are not always accurate.

“These people aren't fact checking the books, they're trying to turn them around as quickly as possible to make money off of following a fad and following the interest,” Aon said. “They just want it to have a catchy title and they want people to buy it instead because maybe it's cheaper, or maybe it has prettier pictures on the cover.”

Aon believes AI could be helpful in the identification of some common species, but it should never be relied on for edibility. Readers who are unfamiliar with the content or choose to trust content that is inaccurate could be putting themselves in a life or death situation.

Amazon has taken down some of the AI-generated foraging books amid backlash and the tech giant now requires authors to disclose if their books are AI-generated. But verifying that can be tricky, and it’s always possible for new AI-written books to replace the old ones. Some foraging experts have already issued warnings to their followers on social media.

“It might be years before we have actual regulations around this sort of topic,” Aon said. “I think private companies, especially large sellers like Amazon or others, have the responsibility to be more responsive.”

Aon said it’s best to stick with well-known authors in the foraging community and research them thoroughly, as they have more knowledge to share than what a computer could dig up.

“No one can replicate another person's personal touch in a book, and they can't replicate their experiences that they're sharing,” he said. “They can't replicate their stories or their observations. And that's really what makes a good book good.”

He said people should also research book publishers and warned against buying the cheapest or first books available. Some foraging experts Aon recommends are Erica Marciniec of Wild Food Girl and Briana Wiles of Rooted Apothecary.