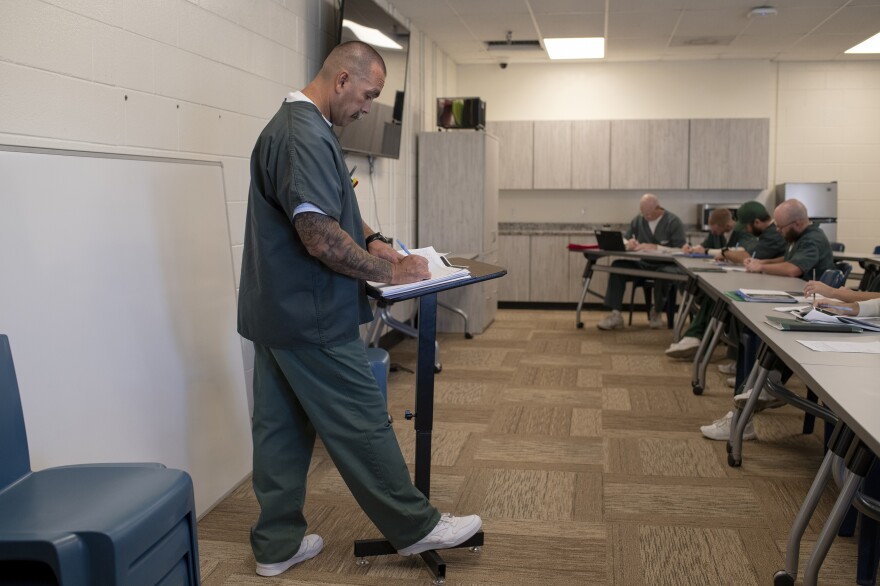

David Carrillo is getting ready for a college class at his Loveland home. He teaches economics to incarcerated students.

“They are introduced to a world beyond what they've known for a very, very long – not just for a very long time, probably ever.”

The 51-year-old Carrillo served nearly three decades in various Colorado prisons for his involvement in a murder that happened in 1993. He became one of the first incarcerated professors to teach other incarcerated students.

Now free, Carrillo still teaches students on the inside at Adams State University and Red Rocks Community College, but overcrowding in state prisons has made it harder to keep classes going. They’re often canceled, and students face obstacles just to get there.

“If you could imagine, you live in your bathroom and now they put in another person in that bathroom with you, and the two of you have to live in that space,” Carrillo said. “That problem then snowballs into other issues.”

What Carrillo describes isn’t just about crowded cells. It’s the result of a corrections system buckling under multiple pressures.

There aren’t enough prison beds. There aren’t enough staff. Stricter parole policies are keeping more people inside.

Together, those pressures led Colorado to activate its Prison Population Management Plan, created in 2018. It helps the Department of Corrections manage capacity when prisons are operating at more than 97% capacity for 30 straight days.

But, under the plan, when the prisons run out of room, Weld County Sheriff Steve Reams says the overflow lands in county jails.

“We’re holding sometimes between 30 and 50 inmates in my facility that are sentenced to the Department of Corrections and should be in the Department of Corrections.”

Reams and more than a dozen county sheriffs warned Gov. Jared Polis in a letter months ago that overcapacity state prisons were pushing inmates into their jails.

Prison staffing shortages add to the strain, according to James Carr, a 31-year-old sergeant at Sterling Correctional Facility.

“We don't have enough staff to do all this,” Carr said. “The stress that COs [Correctional Officers] go through sometimes, I don't think management sees.”

Carr has been working in Corrections for roughly 10 years and is a member of Colorado Workers for Innovative and New Solutions (WINS), a union representing more than 27,000 state employees. He says maintenance workers and teachers are filling in as correctional officers, programs and classes are canceled, and even inmates nearing parole feel uneasy about reentering society.

“An inmate was talking to me. They’re getting ready for the parole board hearing, but they haven't got all their classes done. So, they don't feel like they're ready to go out into the outside world, and they're actually scared,” Carr said. “It seems like when we leave someone, they come back in six months.”

Kyle Giddings also knows the system from the inside. He’s the deputy director of the advocacy group Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition and is formerly incarcerated.

Giddings says Corrections’ policies, including tougher penalties for minor parole violations, like missed appointments, are driving what he calls a “crisis in corrections.”

“The parole board made an internal decision that they're going to start enforcing these technical parole violations more strictly,” Giddings said. “It's causing the prison population to explode.”

Giddings says accountability is missing and that “there’s no oversight panel or commission that oversees and holds DOC [Department of Corrections] accountable.”

Without reform, he believes Colorado could soon have to build its first new prison in more than two decades.

The Legislature’s Joint Budget Committee has approved nearly $3 million for Corrections to add 153 more prison beds. But Democratic state Sen. Julie Gonzales – a sponsor of several prison-reform bills and a Denver Community Corrections Board member – says tough choices are still coming in January when the legislative session begins.

“Do we want to spend millions of dollars on private prison beds, or do we want to spend those dollars on health care, education, transportation?” Gonzales said. “There are very deep ‘yes or no’ binary choices that we are going to have to make with this budget.”

Those choices go beyond budgets and bills for the formerly incarcerated professor, David Carrillo.

He says meaningful change starts with seeing people behind bars as capable of growth and purpose beyond their past.

“I went in at 19 years old. I was a teenager when I went away,” Carrillo said. “Now, I'm a college professor, I'm a consultant, I'm an author, and continuing to contribute and open up opportunities for others.”

In a statement, the Department of Corrections told KUNC it’s working to ease the strain on county jails by hiring more correctional officers. Certain nonviolent offenders could also be released early to help with overcrowding.

The Prison Population Management Plan will remain in place until prison capacity falls below 97% for 30 straight days. Right now, prisons are nearly 98% full.