Ravi Rothenberg stands outside the door of a home in North Boulder. He’s excited, but a little nervous.

“Hey, sir. I'm one of your neighbors here in our Churchill Point Neighborhood,” Rothenberg starts.

Rothenberg is practicing how to invite a stranger to a community event. The interaction is meant to feel awkward.

“I haven’t seen you around before…are you with the city?” says Ian Leahy, his door-knocking partner, pretending to be a neighbor who is a bit standoffish.

“No, great question,” Rothenberg said. “(I’m) just a guy looking to create a place for my kids to grow up and know some of their neighbors.”

Rothenberg finishes up his spiel and leaves the flyer with his “neighbor” before Leahy closes the door. They debrief afterwards.

“I was enthusiastic and clear, but I didn't, like, ask you so many questions,” Rothenberg said.

Rothenberg is participating in the Neighborhood Village Project. It’s a relatively new 10-week program designed to help neighbors get to know each other. Knocking on doors is just one of the ways they will reach out to people, but they'll also host events and follow-up with people over text.

Rothenberg joined the program because he missed the kind of neighborhood he grew up in back in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

“We had snowball fights and made up games and could go up to a friend's house and ring their doorbell and just ask if, you know, somebody was home and wanted to play,” he said.

He’ll wave at his neighbors in Lafayette but he doesn’t know their names.

“It feels safe and friendly, but surface level,” he said. “We've culturally lost the village mentality.”

The Neighborhood Village Project wants to bring back that type of community. Members attend weekly meetings where they get step-by-step guidance on how to meet their neighbors by creating engaging flyers or thoughtfully inviting people to events.

Savannah Kruger founded the program after having several stiff interactions with her own neighbors in Boulder. Before that, she had lived in housing co-ops and saw how fruitful they were — people made food for each other, talked about their days and supported one another. She wanted the same in her current apartment, but she knew it would take some work.

“My partner was like, ‘Do we really need to knock on these doors? Can't we just, like, put a flyer up somewhere?’” Kruger said. “And I was like, ‘It's not gonna work. We have to actually make contact. We have to do the uncomfortable thing of connecting first and putting ourselves out there.”

Since Kruger started the Neighborhood Village Project last June, around 130 people have participated from all over. There’s in-person cohorts in Boulder and Denver, as well as people participating online in places like Honduras and Australia.

This isn’t a new concept. But Kruger said accountability matters. Intention is only as good as the action behind it.

“Life is busy. There’s so much going on,” she said. “I say ‘I want neighborhood community,’ but I actually need to, like, do a specific set of things over a span of time and stay committed.”

Kruger has seen success. Neighbors who avoided eye contact before are now having dinner together, sharing household tools, and actually becoming friends.

“We don't need to be building like our perfect housing situation in the middle of nowhere and escape society, we need to make society better,” Kruger said. “So let's do that where we already live.”

A recent Pew Research Center study found that around three-quarters of Americans know some or none of their neighbors. Less than half say they trust them.

David Burton is a community development specialist and researcher with the University of Missouri Extension. Last year, he conducted a study, asking people to identify the qualities of a good neighbor. Two key traits rose to the top.

“We now say a good neighbor is someone who's quiet and leaves me alone,” Burton said. “That is a dramatic cultural shift.”

People often point to the COVID-19 outbreak as the culprit, but Burton said that pandemic-era isolation isn't the whole story. People are busy and addicted to screens. Some researchers even blame air conditioning, he said. On top of all this, we don’t like to be vulnerable – let alone with our neighbors.

“We see our home more as a fortress, not a front porch,” he said. “I hear people say sometimes that their home is their fortress of solitude, which is great for Superman, but not so good for us.”

But this is about more than just making another friend or having someone grab your mail. It’s about building trust and inclusion with those right next door.

“When you can get your residents to have a sense of belonging, they're more likely to have civic pride and volunteer and take part in doing things that help shape and improve your community,” he said.

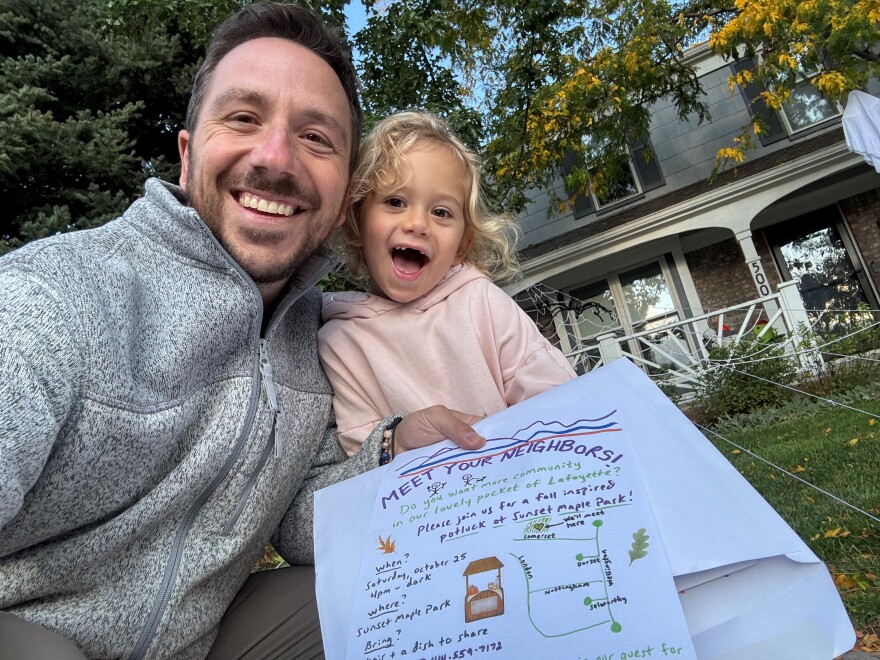

Rothenberg did just that with the Neighborhood Village Project. Day after day, he knocked on doors and posted hand-drawn flyers around the neighborhood, inviting people to his first community event – a potluck in his neighborhood park.

Rothenberg wasn’t sure how it would go or who would show up.

“(I have) some nerves around you know, are people gonna embrace this or resist it,” he said. “And do I have actually the capacity to really step forward into it?

But within the first hour, around 50 people were there. Andy Welch decided to swing by after seeing his neighbors walk over to the park. He’s been in the neighborhood since 1983, but there haven't been many events.

“There was one in my cul-de-sac years ago, and boy, that probably was over 15 years ago,” he said. “I don't recall anything like this ever before. So I think it's a great idea.”

Welch isn’t the only one who feels that way. Taylor Appling has wanted this for a while. She was going to host her own event, but time got away from her. Then she saw Rothenberg’s flyer on the community mailbox.

“We were like, ‘Oh yay, somebody is taking action and putting it together,’” she said.

Appling has been in the neighborhood for 14 years. She’s excited to make some new connections.

“I just like the idea of being friendly with the people that you're right around,” she said. “I think we're in a time and place where we could easily not pay attention to each other, so I think it's just a really nice way to look up.”

Rothenberg plans to host one more neighborhood event before his cohort of the Neighborhood Village Project ends in December.